For Australia to become more inclusive—where no one is left behind—children need to be front of mind for policymakers when developing and implementing our post-Covid recovery framework.

As a prosperous nation, Australia should be one of the best countries in the world to be a child. But it’s not. According to a 2020 UNICEF report ranking rich countries on child wellbeing outcomes, Australia ranks 32 out of 38 rich countries for child wellbeing. We rank 35 out of 38 countries for children’s mental wellbeing.

Australia might be considered the lucky country, but with complex economic and social challenges on our horizon, luck will not be enough to set up future generations for success.

One way we can improve outcomes for children is to follow the money. Governments often spruik their budgets as having “something for everyone”. However, it is rare that Australian budgets pay specific attention to children.

A brief analysis of Commonwealth Budget speeches demonstrates that children are mentioned infrequently. In the 2021-22 Budget, “children” was mentioned three times in the context of the announcements on women’s safety, while “child” was mentioned once in the context of preschool funding. Additional childcare funding was also announced, but this was in the context of workforce participation, particularly for women, rather than to improve outcomes for children. In the 2017-18 Budget, “child” or “children” were mentioned seven times with reference to programs addressing family justice, child exploitation, child sexual abuse, children’s cancer, schools funding, and childcare.

One meaningful way to address this policy gap and put children front and centre of policymaking is through child-responsive budgeting.

What is child responsive budgeting?

While national and subnational budgets allocate resources to address the needs of children (i.e., through funding for education), thinking about children explicitly while constructing a budget, rather than retrospectively, is a relatively new practice.

A child friendly budget is one that adequately addresses children’s issues, such as poverty, malnutrition, illiteracy or child protection. The child friendly budget rests heavily on the system upon which it is constructed, implemented, and evaluated.

Deliberate investments in children will yield future returns by producing a healthy and productive workforce. Greater public investment in children is also likely to result in higher earnings, reduced crime and reduced welfare dependence.

Like gender responsive budgeting, a child responsive budget is not a separate budget for children. Rather, it is a tool to consider the current and future needs of children when developing policy and allocating resources. It is also a way to examine how policy change, as well as changing socio-economic factors, can impact children.

Which countries use elements of child responsive budgeting?

In Scotland, the government introduced the “Getting it Right for Every Child” policy with eight wellbeing indicators to guide engagement with children and young people. Elements of this were enshrined in legislation in 2014. Recognising that enhancing income support to low-income families was vital to improving outcomes for children and young people, the Scottish Government doubled its child payment in 2021. Advocacy group Children in Scotland have called for budgets to be built for children’s wellbeing to address the fundamental causes of inequality and other long-term systemic challenges. It argues that making Scotland the best place for children to grow up is about more than just outcomes-based budgeting, but about systems-change governing.

In New Zealand, there is a Child Wellbeing and Poverty Reduction Group that sits in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Prime Minister and Minister for Child Poverty Reduction, Jacinda Ardern, wants New Zealand to be the best place in the world to be a child. The Group is leading the development and implementation of New Zealand’s first wellbeing strategy for children and young people. There are signs that its focus on children is paying off: in February 2022, Prime Minister Ardern announced that child poverty was continuing on a downward trend with an additional 66,500 children lifted out of poverty.

In 2019, New Zealand introduced its first “wellbeing” budget. While not specifically targeting children, the approach moves beyond just looking at economic metrics such as GDP, to include a much broader range of outcomes—including human health, safety and flourishing—to assess the success of policies. While it is debated whether wellbeing budgeting has been successful, New Zealand has been able to shift the conversation away from economic growth as being the primary metric of national success.

Putting children at the centre of Australian policy

How can we think about policy making in a child-centred way? Here is what policy could look like if it was designed and implemented to be more child-centric.

Child-centred childcare policy

In many policy documents on childcare funding in Australia, the focus is on the improvements to workforce participation, particularly for mothers, and childcare affordability, rather than funding and delivering child-centric early childhood education. Policy commitments could focus on ensuring the best quality early childhood education for children—from infrastructure and curriculum, to ensuring our early childhood educators are highly skilled and renumerated accordingly.

Paid Parental Leave

Increasing the amount of Paid Parental Leave available to parents, particularly fathers, will yield many benefits for children, including improvements to emotional and physical health and greater diversity of day-to-day role models. Studies identify positive links between father engagement and child development, including greater cognitive ability, superior emotional development and higher social aptitude.

Income support

A very high proportion of children experiencing poverty live in families who rely on government payments. Permanently increasing these payments, including JobSeeker, family and single parent payments will reduce child poverty. In Johann Hari’s book Stolen Focus, he cites a large study by the British Office of National Statistics which found that if there is a financial crisis in the family, a child’s chances of being diagnosed with attention problems goes up by 50 per cent. If a parent must make a court appearance it goes up by nearly 200 per cent.

A UNICEF report found that the factor that had the strongest impact on a child’s wellbeing was being able to spend time with family. Providing additional income support to those families on low incomes, who may need to work multiple jobs, would free up time and the headspace for parents to spend additional time with their children.

Climate change

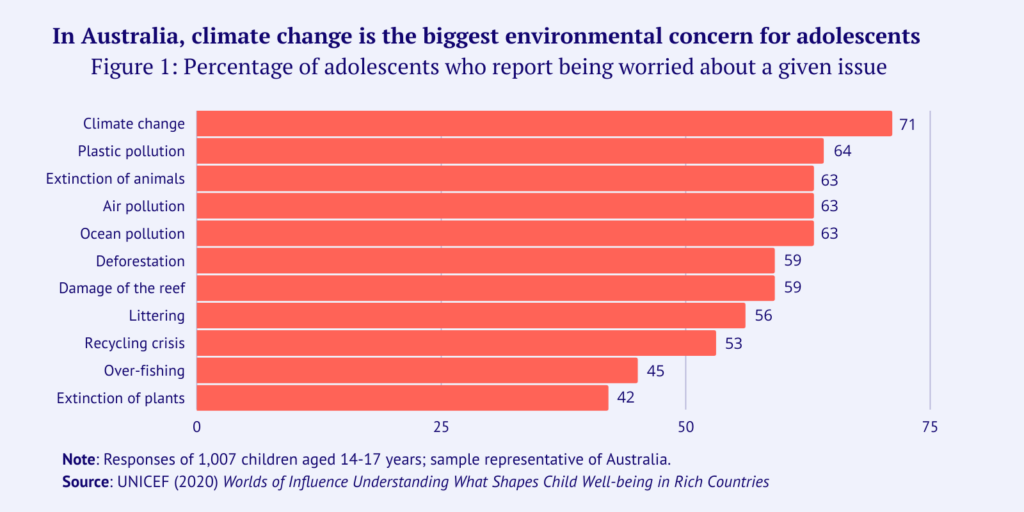

In Australia, 59 per cent of young people consider climate change to be a threat to their safety and 71 per cent name it as their biggest environmental concern. Three out of four adolescents in Australia want their government to act on climate change. There is emerging research that demonstrates that integrating child-centred climate change adaptation initiatives into the community can build the resilience of households and communities, as well as of children.

Making child responsive budgeting a reality in Australia

Here are six big ideas that could shift the dial on how we think about children and their place in Australian policymaking.

- Advocate for analysis of the 2023-24 Budget from a child-centred perspective. This would lay bare how much of the budget focusses on children—and what proportion of spending goes beyond funding to the states and territories for education and health.

- Call for greater analysis of children in the policy development process. Real change in public policy requires consideration of children at the earliest stages of policy development, not simply reporting child-related measures as an afterthought in budget papers. This will require cultural change and prioritisation of children in government policymaking processes, which will take training and leadership across the public service and consistent demand for child-centred policymaking from decision makers.

- Advocate for better data to underscore the importance of improved public investment in children. Governments rely heavily on data to tell the story of policy successes. Efforts to delve into the experience of other countries, especially OECD and G20 economies, to inform Australian policy would be welcomed.

- Advocate for the next national Intergenerational Report to include analysis on the future trajectory and needs of Australia’s children. The Intergenerational Report is heavily skewed towards analysis of Australia’s ageing population. Including analysis on the future needs of Australian children will be important to highlight policymaking gaps, as well as opportunities to think about the future of work and the future of the economy. We must invest in these areas now to ensure Australian children will have the tools to thrive in the next economy.

- Encourage peak bodies and interest groups to develop policy ideas for a child-centred budget. Policymakers are very receptive to evidence-based policy ideas generated outside of government. Groups should start to think about what the centrepiece of a child-centred budget would be.

- Socialising and promoting the idea of child responsive budgets is a great first step. Encouraging policymakers to think about the issue—and perhaps include it as a “fresh new idea” in briefings for the new government could be all that is needed to pique the interest of a minister looking to make a mark.

Dr Alicia Mollaun is the Senior Manager for Economic Policy at Equity Economics and Development Partners, a firm committed developing solutions to complex challenges domestically and internationally through more inclusive growth. Alicia has previously worked at the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and in the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, the Hon. Julia Gillard, MP. Alicia has a PhD in Public Policy from the Crawford School at the Australian National University.