Adverse Childhood Experiences: Pathways to better policy and practice with First Nations

The Adverse Childhood Experiences model lacks a First Nations lens. Focusing on early interventions and culturally safe, community-led strategies, as well as enhanced data collection, would improve health equity.

12 February 2025

In Australia, an estimated 72 per cent of children experience at least one Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE), which is associated with significant adverse health and educational consequences. These include increased risks of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, substance abuse and higher mortality rates. Vulnerable groups, including First Nations populations, are disproportionately affected, facing higher prevalence of ACEs and compounded intergenerational trauma, which further amplifies these health risks.

To address this, inclusive approaches to treatment and research are needed that provide a more accurate understanding of ACE prevalence and impacts. This would facilitate culturally informed, evidence-based policies that better address the needs of Australia’s First Nations communities, as well as other marginalised groups.

Understanding Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) refer to traumatic events affecting children aged under 18, including abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, parental divorce or domestic violence, as well as broader socioeconomic adversities. These experiences can significantly harm physical, mental and social wellbeing, often persisting across generations.

The impacts of ACEs are influenced by environmental factors and gender differences. Studies show higher ACE prevalence among girls, while boys often face greater long-term mortality risks. Additionally, ACEs are associated with pregnancy-related depression. Environmental factors, including access to green spaces, can mitigate ACE impacts – though these potential mitigating influences are often less accessible to socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

Addressing ACEs requires intersectoral approaches and targeted public health policies. Comprehensive research and policy changes must account for gender disparities, socioeconomic conditions and environmental factors to create effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Breaking the cycle of trauma and promoting equity with First Nations

Though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognises ACEs as a global public health priority, data on First Nations communities is often incomplete or absent in research. This data gap stems from an overreliance on urban-centric studies and administrative datasets that fail to account for the lived realities of First Nations communities, particularly those in rural or remote areas. To address this, more inclusive methodologies are needed, such as integrating child protective services records with parents’ ACE histories. This approach could provide a more accurate understanding of ACE prevalence and impacts.

For First Nations Australians, addressing ACEs is central to breaking cycles of intergenerational trauma. Systemic reforms in policing, housing and healthcare – combined with investments in prevention – are essential to reducing the long-term social and economic burdens of ACEs. For example, ACE-related trauma is estimated to cost Australia $6.8 billion annually, emphasising the need for preventive measures that not only improve health outcomes but also reduce costs.

Responses must be led by First Nations people and communities, ensuring that cultural knowledge and lived experiences shape program design and policy. Supporting First Nations research practices and expanding surveillance systems to include diverse data sources are key steps toward equity. Additionally, fostering safe, stable and nurturing environments is vital for empowering children to reach their full potential.

In the development of future policy in Australia, a comprehensive approach is crucial for achieving transformative change and health equity. ACE research must be integrated with preventive policies to foster community-driven solutions.

A policy agenda for addressing ACEs

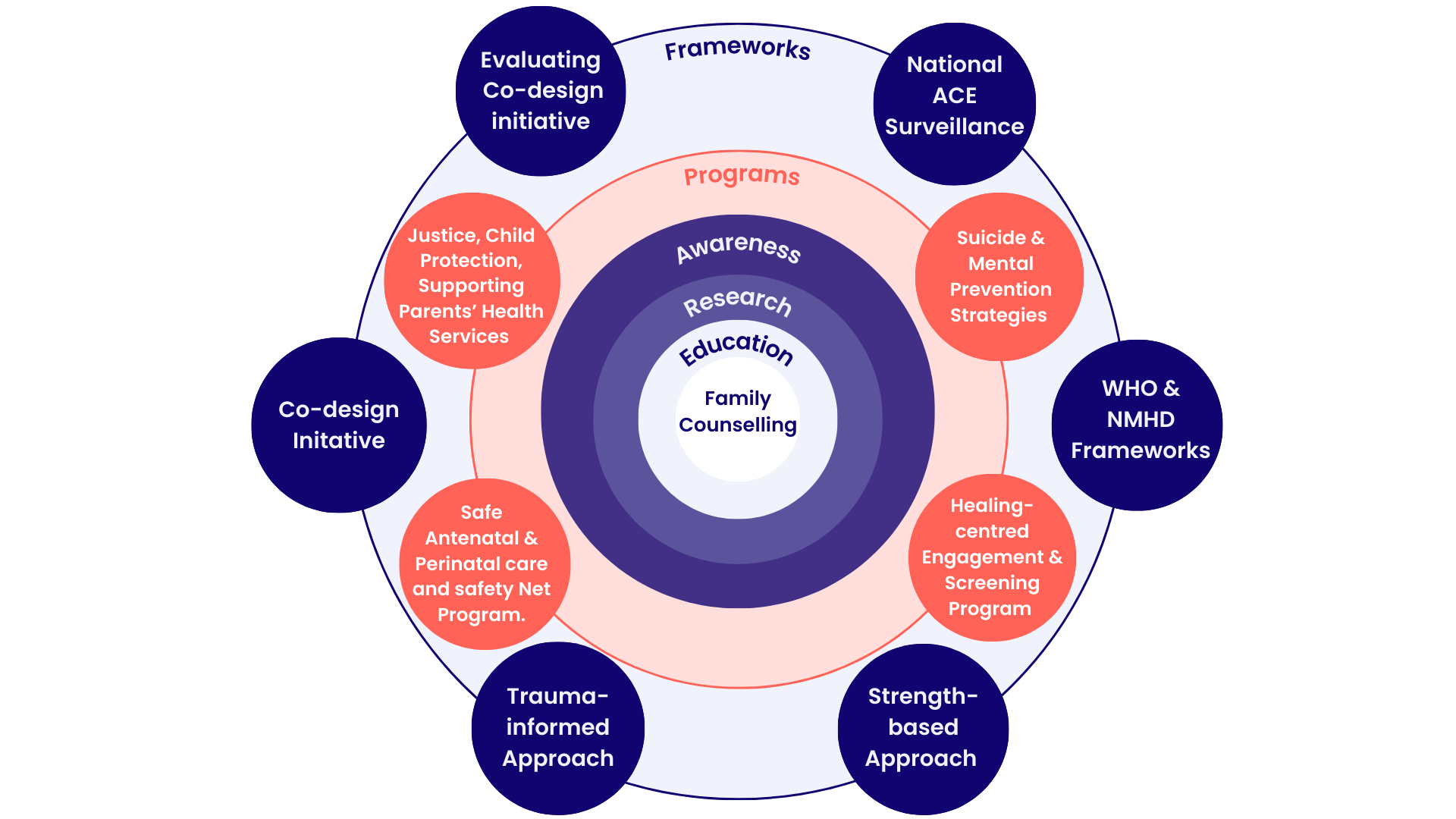

While the ACE model informs mainstream health policy in Australia, its limited integration of First Nations perspectives underscores disparities. Given the higher prevalence of ACEs among First Nations peoples, culturally safe and community-led approaches are essential. Enhanced surveillance, co-designed programs, evaluating co-designed strategies and integrated data systems could foster equitable health outcomes and responsive policies. This approach is summarised in Figure 1, which integrates the ACE framework with preventative health guidelines for First Nations people.

Figure 1: Proposed approach for integrating the ACE framework into preventative health for First Nations

By integrating these principles with ongoing research and proven global practices, ACE responses can promote resilience, relational health and sustainable solutions for vulnerable populations.

Building on this model, I also propose six key principles to inform health policy responses to better address the needs of First Nations people and communities in Australia.

- Culturally safe and community-driven approaches: Responses to ACEs, particularly for First Nations populations, must prioritise culturally safe, co-designed interventions that respect historical, social and cultural contexts. Tailoring solutions to specific community needs ensures their relevance and effectiveness.

- Gender-specific and trauma-informed care: Programs for First Nations women should explore the gender-specific health impacts of ACEs, including links to chronic conditions such as diabetes, and the role of interventions such as physical activity in mitigating risks. Culturally tailored antenatal and perinatal care are also essential.

- Multidisciplinary coordination: Effective responses require collaboration across justice, child protection, health and social services, integrating efforts to address poverty, inequality, food security and safety nets for vulnerable populations.

- Screening and early intervention: Improved ACE screening tools, integrated into routine prenatal and paediatric care (as implemented in California), and early interventions such as the ACT Kindergarten Health Check, can help identify and address ACE-related risks early.

- Policy reforms and structural changes: Policies must address systemic issues such as poverty, inequality and discrimination. Reforms in policing, justice and education systems are essential to reducing discrimination and fostering reconciliation.

- Healing-centred engagement: Personalised networks of referral and treatment plans, supported by pilot trials in First Nations contexts, are critical for addressing unique challenges and fostering holistic healing.

To apply these principles, policymakers need to draw on best practice from Australia and internationally to design health responses and programs for ACEs.

Australia has implemented several initiatives to address ACEs and mitigate their long-term effects. In Queensland, the Speak Up, Be Strong, Be Heard initiative employs culturally sensitive outreach strategies to reduce ACE-related harm, particularly among vulnerable communities. Meanwhile, the ACT Kindergarten Health Check provides early screening to identify developmental vulnerabilities in children, allowing for timely interventions.

Globally, various models have been adopted to support children affected by ACEs. Scotland and New Zealand have developed trauma-informed approaches in their education systems that create safe learning environments and equip educators with the skills to support children experiencing adversity. In Brazil, community parenting programs focus on promoting positive parenting practices to help mitigate childhood trauma. Similarly, in China, parent-focused education initiatives aim to reduce harsh parenting practices and foster healthier family dynamics.

Canada, India and several European nations such as the Netherlands and Finland, have integrated mental health services, poverty alleviation programs and community-led initiatives to address the prevalence and impact of ACEs. A recent study emphasises the role of positive childhood experiences (PCEs) in mental health, providing evidence from India with broader implications for low- and middle-income countries. These comprehensive approaches recognise the multifaceted nature of childhood adversity and the importance of early intervention, education and community support in fostering resilience.

Community health hubs in metropolitan Australia offer family-centred care for at-risk families, but referrals remain low. Integrated care models, including care navigators and home visits, could enhance continuity and outcomes. Future policy and interventions could integrate health and social care services to better support families affected by ACEs.

Areas for further research

Further research on ACEs will also improve the effectiveness of policy responses. I have identified five potential focus areas:

- Evaluating best practices: Rigorous evaluations are needed to identify the most effective interventions for mitigating ACE-related health impacts, especially in diverse sociocultural contexts.

- First Nations-specific research: Explore how structural changes, such as enhanced safety net programs, can better support First Nations families and communities.

- Technology-assisted parenting programs: Examine how digital tools can empower parents and foster positive family dynamics in preventing ACEs.

- Generational impacts: Investigate how a parents’ own ACEs influence the health and wellbeing of their children and identify therapeutic targets for breaking cycles of intergenerational trauma.

- Integrated payment models: Explore payment structures that allow extended in-clinic time for family focused discussions and therapeutic interventions.

Above all, policymakers, clinicians and health services must allocate resources and actively engage in initiatives that promote employment and maximise opportunities to access stable household environment, healthcare and physical activity.

Dr Shakeel Mahmood is a research fellow at Charles Sturt University specialising in culturally sensitive health policy. With over 20 years of expertise in health policy, qualitative analysis, and monitoring frameworks, he has worked with the international health reseaerch organisation ICDDR,B and universities globally. He holds a PhD in Health Policy and a MPA from the Universty of Maine, as well as a MBA from Trinity University.

Image credit: Travis De Vries

Features

Libby Hackett, Jordan Ward, Jack Isherwood, Bonnie Bley, Hannah Lobb, Isabella Whealing and Hugh Piper

Subscribe to The Policymaker

Explore more articles

Libby Hackett, Jordan Ward, Jack Isherwood, Bonnie Bley, Hannah Lobb, Isabella Whealing and Hugh Piper

Features

Libby Hackett, Jordan Ward, Jack Isherwood, Bonnie Bley, Hannah Lobb, Isabella Whealing and Hugh Piper

Explore more articles

Libby Hackett, Jordan Ward, Jack Isherwood, Bonnie Bley, Hannah Lobb, Isabella Whealing and Hugh Piper

Subscribe to The Policymaker