6 December 2023

Let me start with the story of a child I know who spent the first years of his life in a violent and unpredictable environment, who likely experienced drugs in utero. A child whose grandmother was overlooked as a carer due to not “engaging well” with government services and the fact she lived in a one-bedroom apartment from Housing NSW (children need to have their own bedroom to meet the regulator’s standards).

Fast forward to when I met this child, now 11 years old. 54 foster families had told the child they could not live with him anymore, before being moved between six group homes and eventually to live in a hotel. An isolated child, wired for survival in the system, when I asked him what he was good at he told me: “respite”, a system term referring to a service when carers need a break from the child. As a society we were paying close to $1 million a year on services for him that were likely to cause more harm.

At this point we might cast our mind back to the grandmother who loved her grandson and wonder if the investment in time to share a meal before asking system questions might have been worth it. Could we have shown vulnerability and sat with risk and considered her couch while we looked for appropriate housing and support?

Anyone who has spent time in group homes has stepped into the pain I am describing and understands the urgency. The urgency of a child surrounded by workers busily writing forms but who is going to bed tonight not knowing who will be on shift with them tomorrow, not loved or held, but warehoused.

Since the 1980s, at least 14 successive inquiries, reports and government-led reforms in NSW have aimed to improve outcomes for children and young people in the child protection and Out of Home Care (OOHC) systems. They have done much to strengthen legislative and bureaucratic frameworks – however, for too many children and young people, the experience of care remains unacceptably poor. We do not need another decade of inquiries – we need leadership committed to robust and widespread cultural change, now.

Humans need relationships – children in care are no different. Without relational security with safe, attuned adults, our interventions are destined to fail. We know a lot about brain development, attachment and trauma, yet we have not put it into practice. Instead, we have a structure that:

- orientates practice to what can be easily measured rather than what people in the system tell us is meaningful;

- sees frontline workers spend the vast majority of their time keeping the system safe with paperwork and meetings, leaving them with no time for people;

- promotes relational deprivation through the uniform application of clinical-medical concepts of care;

- does not support long-term stable relationships with either families or substitute care givers; and

- does not drive or sustain innovation.

Further, in attempting to prevent immediate harm to children, this system often (unintentionally) causes further harm.

We are letting our kids down.

The “anxious” care system

The most important thing for vulnerable children is a primary care figure who they know cares about them, listens to them and displays empathy. And yet we currently put the system’s safety above all else. We spend our time writing notes, collecting data, doing checklists and filling in forms.

Compliance activities are effective only to a point: they are somewhat useful in screening and eliminating candidate carers and workers who may cause harm, they are useful in ensuring that carers understand their obligations, they are useful in making sure that organisations conduct themselves ethically. These are important things. However, they are not effective in achieving positive, lasting outcomes for vulnerable young people.

Parents rarely complete forms about their own child’s wellbeing and they rarely scale or rate their children’s behaviours. It would be unusual for a parent to require a checklist to know how to assess risk and it would be unlikely that a parent would ever draw up a case plan for the year ahead. Yet, at present, our frontline workers spend their time writing notes, collecting data on behavioural issues, doing checks, filling in forms, reporting on carers. Moreover, we ask organisations to demonstrate all of their activities via measures and outcome reporting. When something goes wrong, we simply increase these accountability measures.

A charitable interpretation of this practice is that it is a poor attempt to remove risk. A less charitable interpretation is that it is a public performance where the Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) and NGOs discharge their duty of care, showing little regard for whether a new measure achieves anything other than the appearance of greater diligence. All of this is maintained by DCJ, our judicial system and the Office of the Children’s Guardian. These “technical” forms of safety are not just a poor substitute for an attuned adult: by constraining and limiting time for relationships, they are a significant contributor to poorer outcomes.

Why is this the dominant paradigm? Because it does a good job at keeping the system safe. And because caring adults within the sector have struggled to acknowledge that we prioritise actions that reduce our own anxiety and liabilities. Actions which ensure the immediate physical safety of a child reduce our anxiety.

Conversely, acknowledging the alternate forms of harm these actions have on children in the medium or long term requires us to hold a different lens to what we do and how we work to achieve change. For example, we feel good about removing a child from immediate harm. Our worries (and liabilities) decrease when safety and case plans are in place. But we do not like to acknowledge that many of these children end up bouncing around foster placements or living in hotels or institutions where they are deprived of relationships or a normal experience of childhood.

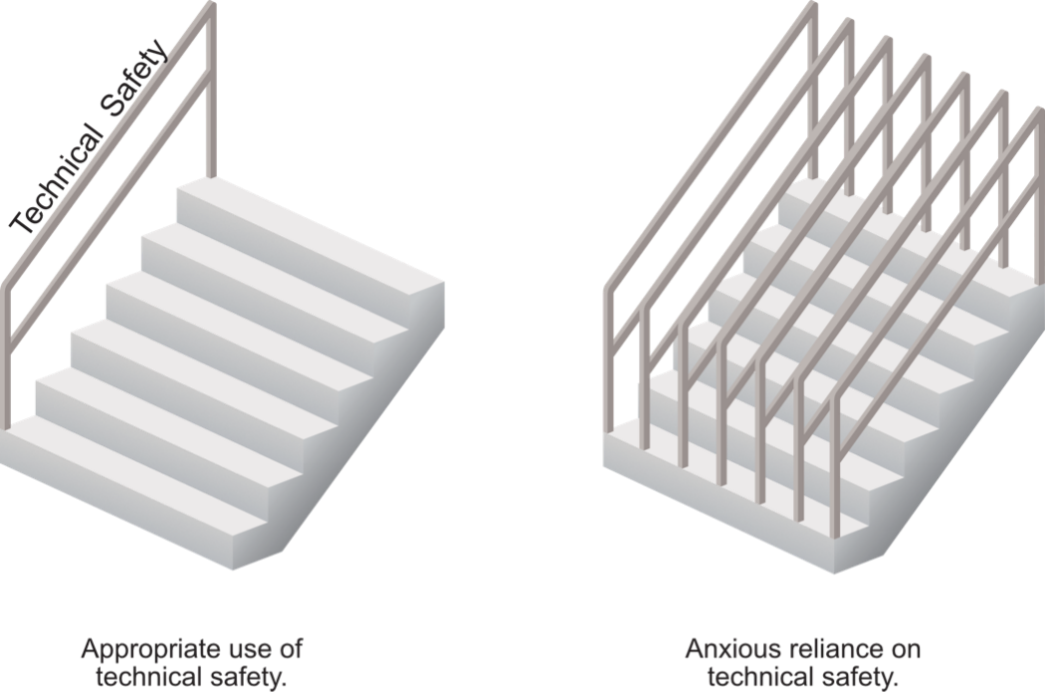

This “technical” safety is like a handrail, at best stopping those on the edge of the staircase from falling off or making it easier to climb stairs. The goal itself is to learn to effectively climb the staircase, namely that children in care grow to be happy and connected and productive. After we have installed one handrail there is little to no gain by installing five more. Indeed, in extreme circumstances like our OOHC system, we have so many handrails that it can actually impede children healing and discourage carers. We have a system that is spending the majority of its time installing, thinking about and perfecting handrails.

“Best practice” and outcomes measured

We also need to consider how we measure outcomes, what we choose to measure, and how these choices impact policy and practice. Deeper thinking and a willingness to innovate beyond simple tangible quantitative measures is essential.

OOHC systems are under-resourced and experience high levels of unpredictability. Adults or systems under stress are less likely to be curious about alternative perspectives or act without explicit consensus. Therefore, “safe practice” in OOHC has prioritised certain actions that are based on documentable information and has marginalised subjective interpretation of experience. We over-emphasise quantitative measures, and ignore or disregard qualitative methods or interpretive approaches as being “not objective”. However, are we simply recording one set of data, such as physical safety, at the exclusion of other sets of data, such as young person’s experience of living in a hotel staffed by shift workers?

Being unable to easily quantify aspects of life does not mean that these are not the most important aspects. If we want to understand or improve a young person’s experience of being in OOHC, there is likely no check list, plan or questionnaire that will do this satisfactorily. This does not mean that we cannot understand it, but rather that we are asking the wrong questions in the wrong ways. To understand what meaning and wellbeing look like in life, we would need to ask open, curious, qualitative questions in the context of a respectful engagement. We need to focus on the lasting relationship opportunities for young people because we know that this is the key factor in healing trauma.

Why do families who are struggling not welcome the “help” offered by child protection workers? It is hard to think of any multi-billion-dollar sector that is less interested in why its primary audience passionately dislikes it. We do not ask them, or ourselves, what services would be welcome.

Children who experience current harm in OOHC are actively excluded from research that informs “best practice”. Evaluating therapeutic outcomes for children experiencing current harm is difficult and leads to evaluation practices primarily informed by an understanding of “safe enough” children. This does not reflect the lived experience of many children in care. The most obvious example of this is that efforts to understand children’s experiences of care are most likely to be informed by families who have the time and capacity to meaningfully answer questionnaires or participate in interviews. We know that children who have been harmed by adults and moved between families time and again will struggle to connect with these efforts. Research and evaluation in the sector has a strong emphasis on measuring the physical over the relational, which is in contrast to what achieves positive outcomes.

We need a methodology that is fit for purpose, one that helps us orientate to what people affected by the system tell us is meaningful, not just what is easy to measure.

Real relationships, not professional detachment

Our current interventions are built on clinical and medical concepts of care – they promote a one-size-fits-all “professional distance” approach. This makes sense when seeing a “client” for one hour a month, but when used to raise a child who has lived in a hotel for two years, professional distance causes relational deprivation by impeding connections.

Interpersonal boundaries in the context of OOHC need to promote carer attachment and lifelong connections. We need to rethink our professional and organisational ideas about boundaries to enable these children to have experiences of being appropriately nurtured. Adults who work with them should not just be playing a “role”, they should be genuinely open and connecting with the young person, attuning to them, relating to them. They should self-disclose as they would with other children in their lives, and should question themselves as to why they would not do so. They should be allowed to give, receive and express affection, and set appropriate, contextual interpersonal boundaries as any parent, friend or relative would.

Taking a relationship-based approach means that the young person can heal and learn through everyday experiences, like cooking, playing sport or resolving a conflict with others, as opposed to having a program or resource taught to them. Essentially, they learn to trust and attach again. They learn how to relate because they experience reciprocity in a relationship with a primary care giver.

I have never met a young person who says it was paperwork that changed their life; they say it was Tom or Rhonda. Paperwork doesn’t change people’s lives. People do.

The need for a paradigm shift: child connection

The OOHC sector has many people who care deeply about children and young people. However, given the outcomes, are we really focusing on the right things, and are we fully understanding the problems we are facing?

What if instead of asking “how do we keep this child safe?”, we instead asked: “what do we need to do to help this child be connected, and through these connections thrive (and hence be kept safe over the long term)?”. What if instead of saying “providers need to deliver services in this way”, we said, “providers need to show how their decisions and actions result in children and young people being connected to others”? What if we could build a system not just around ensuring a house to live in and a school to attend, but equally around ensuring that each child has at least one person, and hopefully a whole network, who knows them and genuinely cares about them? What if we strove to build a system based on relationships?

We can achieve relational practices on a systemic level

The interventions that exist in OOHC primarily meet the needs of government, all levels of our bureaucracy, and all levels of the designated agency. Moreover, they exist within one cultural paradigm. To truly change our OOHC system we must understand the cultural context, where power currently lies and our inherent self-interest. This is especially true when looking at care for First Nations young people who are grossly over-represented in our “care” systems. Advocates have long asked for self-determination. Culturally informed, relationship-based family preservation and the expansion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-led organisations are undoubtably foundation stones for progress. But how do we expect these new interventions to take place if we accredit, procure and monitor these endeavours under the current frameworks?

When we re-orient our institutions and systems to prioritise relationships, then we will see real and meaningful changes; the research tells us so. This has been implemented successfully in other jurisdictions such as Germany through the Individual Social Pedagogy model, with Professional Individualised Care (PIC) implementing this model in NSW with great success. Other organisations working with youth-at-risk such as BackTrack Youth Works are applying these principles to achieve connections and positive outcomes for young people for whom traditional approaches are failing to reach. Family by Family, DCJ’s MOPS program and relational models run by Aboriginal-controlled organisations provide further examples. Insight from such programs can be the basis for legislation, policy and best practice in OOHC – but to date such organisations remain an exception to the rule in the NSW care sector.

Our policies and laws must do more than just rescue children from danger. They must at the same time drive us to consider what is in the best interests of children, to lead practice away from traditional case work and toward offering rich childhood experiences to those in our care. We need more than a child protection system, we need a child connection system.

Now is the time to act

We need to shift our current policy and regulatory framework to promote relationship-based practice. When procurement and contracting is occurring for programs and services, funders need to shift the sector toward relationship-based approaches. The regulator needs to consider how it will reduce bureaucratic burden for carers and free up NGOs to innovate. The NGO sector will need to grapple with how to move forward with ideas of professional nearness, and grow our comfort with, and ability to think about, risk management differently.

We encourage every organisation to conceptualise what relationship-based practice will look like in their context. There is no one way of “doing” it. Rather, it is a continual reorientation away from rigid systems and processes, and toward people. Relationship based practice is what will create meaningful change. Legislation, standards and forms alone cannot address the challenges we are facing, they simply will not meet the needs of these children. Only people can do that.

Since 2005, Jarrod Wheatley OAM has worked across the social sector, running a Youth Centre, creating programs internationally with refugees and founded innovative, not-for-profit organisations, Street Art Murals Australia (SAMA) and Professional Individualised Care (PIC), where he is the current CEO. Most recently, Jarrod has co-founded the Centre for Relational Care (CRC) to achieve foundational policy, legislative and regulatory changes to the NSW OOHC system.

For this work, Jarrod was named NSW Youth Worker of the Year (2014), NSW Young Australian of the Year (2019) and in 2022, was awarded the Order of Australia Medal.

Image credit: Pixelshot

Features

Subscribe to The Policymaker

Explore more articles

Features

Paul Kelaita & Alison Ritter

Peter Shergold

Explore more articles

Subscribe to The Policymaker