Focusing on both employment law and how we design visas could help address the systemic underpayment of migrant workers.

In Australia in recent years, there has been concern over workplace exploitation of migrant workers. Originating from the 7-Eleven Inquiry that found a large company-wide scam where workers were required to repay sections of their wages back to their employer following payment, thereby circumventing minimum award wages, these concerns led to a series of public inquiries, including most notably one led by Allan Fels and David Cousins, known as the Migrant Worker Taskforce. Some of this taskforce’s recommendations have been implemented to penalise non-compliant employers. Others are still in train and may take on fresh directions under a new Labor government, with a historically different approach to workplace enforcement and employment law than the Liberal-National Coalition.

One key characteristic of this policy area is, however, bipartisan: most policy recommendations and legal changes to date in Australia focus on domestic employment law and punishment of non-compliant employers, rather than changes to Australian immigration law and policy. Changes in immigration law to effect changes to migrant worker exploitation have been largely superficial or have focused on key visas rather than the entire immigration program, such as rebadging the 457 visa as the Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) visa. This change did not really remedy some of the main concerns with the prior visa, but did give it a new name, thereby addressing the reputational damage that the old name represented.

…immigration programs can be designed to minimise workplace exploitation and to increase adherence to workplace rights.

Yet, there are good reasons to believe that any exploitative behaviour on the part of employers could be countered with changes or improvements to both employment and immigration settings. Experts on regulation argue that visa design matters for the capacity of workers to craft convincing legal arguments in their favour when bringing workplace disputes. Good regulatory design might make a difference to the rights of working migrants. Even small regulatory changes could potentially have an impact on outcomes. On this basis, scholars such as Manolo Abella and Graeme Hugo have included visa design in their criteria for evaluating best practices for temporary migration schemes. In other words, immigration programs can be designed to minimise workplace exploitation and to increase adherence to workplace rights.

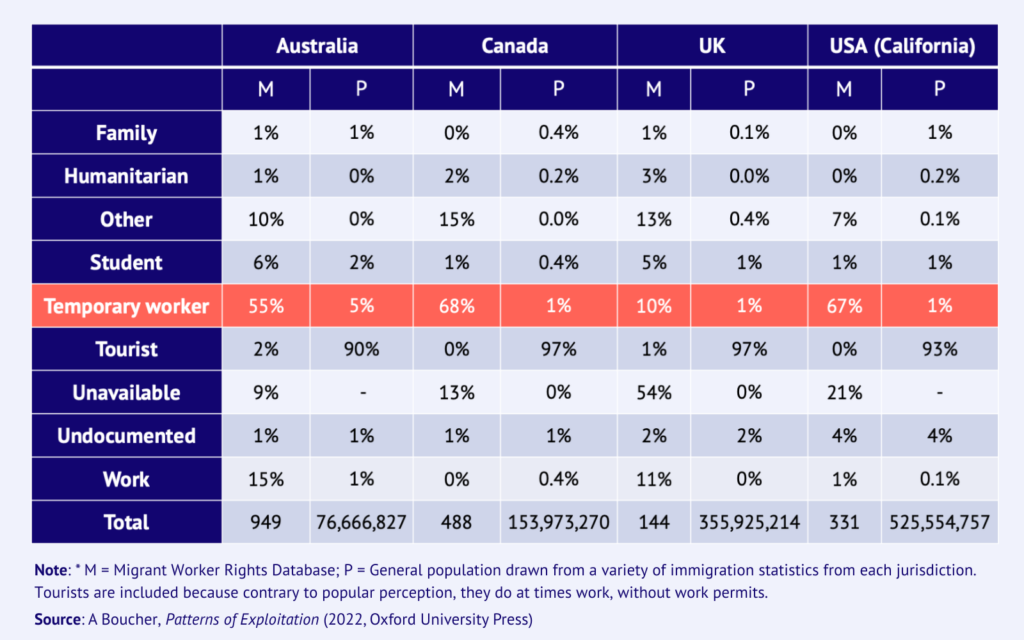

My most recent book, Patterns of Exploitation, demonstrates that temporary migrant workers are disproportionately overrepresented in court and tribunal cases brought by migrant workers. This analysis encompasses 907 court and tribunal cases brought by 1,912 migrant workers in Australia, Canada, the UK and the US.

The overrepresentation of temporary migrant works remains true even factoring in their overall much higher representation within immigration flows than other categories, such as permanent skilled migrants (“work”), spouses (“family”), international students (“students”) or refugees (“humanitarian migrants”).

The table below highlights the rates of temporary migrant workers bringing court cases between 2006 and 2016 as a percentage of:

- The total population of migrants bringing cases over a ten-year period (“M”)

- The general migrant population (“P”)

Temporary migrant workers are disproportionately overrepresented as litigants in claims enforcing workplace rights violations, irrespective of regulatory differences between countries in industrial and employment laws and how they are enforced.

…it is predominately temporary visa status—rather than the details of those temporary visas—that appears to drive this outcome in terms of reported instances of workplace violations.

California, Australia and Canada have very different employment law systems, yet in all, temporary migrant workers are heavily overrepresented as claim-bringers. The United Kingdom is the clear outlier here, however. This probably has more to do with poor immigration data in the UK historically and its strong reliance on migration from EU countries (categorised as “other”) to fill temporary skill shortages (prior to Brexit), rather than reflecting rates of litigation among temporary migrant workers.

Engagement in the labour market does not appear, by itself, to explain this dissonance across major visa types. Although permanent migrant workers are also employed at high rates, and are overrepresented within the database of litigants in Australia (at 15 per cent), they are not overrepresented to the same extent as is the case for temporary migrant workers.

This finding is important because it suggests that it is predominately temporary visa status—rather than the details of those temporary visas—that appears to drive this outcome in terms of reported instances of workplace violations. Being in Australia temporarily on a TSS compared with a Working Holiday Visa, for instance, does not appear to contribute to higher rates of litigated complaints among these migrants—the temporary status overall is the central factor.

Similarly, work visas differ substantially in their design in all four countries yet, outside of the UK which suffers, as noted, from problematic immigration data historically, temporary migrant workers as a broad category are overrepresented in those migrants bringing workplace complaints.

This leads to a central policy recommendation for immigration policymakers: if visa design does influence workers’ propensity to bring violation complaints and, in some instances, to succeed as complainants, it is at the very aggregate level of visa design, namely whether the visa is temporary or permanent, rather than the level of fine regulatory detail.

Small features of visa design do not appear, at least on the available evidence, to make a substantial difference to complaint rates. This may not be surprising as a shared component of temporary visa design is dependency—either on an employer, a sponsor, or certain visa conditions, for ongoing legal immigration status.

From a policy perspective, the core issue therefore appears to be the number of temporary work visas permitted within an overall immigration program compared with permanent migrants and whether the visas permit portability and pathways to permanent status, rather than the minute detail of sub-visa design.

As such, a second policy recommendation is that in consulting around and designing the federal Budget, the levels of permanent and temporary migrant admissions be considered collectively rather than a focus alone on permanent levels. This potentially would also provide the general public with a more detailed understanding of the immigration program and the interaction between temporary and permanent streams. This has likely implications for other areas of policy analysis, such as domestic and migrant worker unemployment.

In short, focusing alone or predominately on employment law will probably not provide the full solution to tackling the issue of the labour market exploitation of migrants. With a new federal government, the time is ripe to bring immigration policy design squarely back into the discussion of workplace conditions of migrant workers.

Anna Boucher is Associate Professor in Public Policy and Comparative Politics at the University of Sydney and a Research Stream Lead at the James Martin Institute for Public Policy. Her book Patterns of Exploitation: Understanding Migrant Worker Rights in Advanced Democracies will be published by Oxford University Press. She has advised the Australian and UK governments, as well as international agencies, on the workplace rights of migrant workers, skilled immigration policy and immigration statistics.