24 July 2024

This article is released ahead of the JMI Policymaker Summit 2024 to offer key insights into the conference’s central theme of intergenerational equity. Learn more and register here.

NSW, like many advanced economies, is struggling to keep up with the demand for social services. Elective surgery waitlist times are growing, the child protection workforce cannot keep up with the number of families who need support, and demand for homelessness services is rapidly rising. These challenges are structural in nature and expected to continue growing, but well-designed preventative services offer hope for improved financial sustainability and wellbeing outcomes in the long term.

Governments worldwide are contending with increasing demand for – and cost of – social services. The NSW Treasury’s Intergenerational Report 2021-22 explained that government spending “is expected to grow faster than the revenue sources that we rely upon” and by 2060-61 there is an expected fiscal gap of 2.6 per cent of Gross State Product (GSP). This forecast was further increased at the 2024-25 Budget to a fiscal gap of 3.1 per cent by 2060-61, showing costs just keep growing. All the services noted above will contribute to this growing pressure on the budget: health expenses are predicted to grow 5.4 per cent a year and social security and welfare is expected to grow 4.7 per cent a year to 2060-61 (on average). This is not sustainable.

NSW is not alone. Most governments inspired by the British welfare state are facing similar pressures. Their policy and funding settings are not generally geared towards curbing the demand issue or addressing escalating costs. Governments find themselves stuck in a hamster wheel, continually needing to inject additional funding for crisis-end services.

Well-designed preventative services can help governments out of this predicament. Early intervention services can better support citizens earlier and build their own capabilities to improve their own wellbeing, eventually reducing demand for crisis-end services. We are seeing the benefits of prevention in NSW already, through programs such as Brighter Beginnings, which are seeking to support children and families early on, so they can have the best possible start in life and better longer-term outcomes.

Finding funding for prevention is still difficult. Innovative approaches are popping up across the world to try and prioritise prevention within state and national budgets. One example is the 2022 UK Independent Review into Children’s Social Care, which laid out a pathway for system reform based on supporting children and families earlier and modelled the costs of doing so.

Long-term modelling holds a key

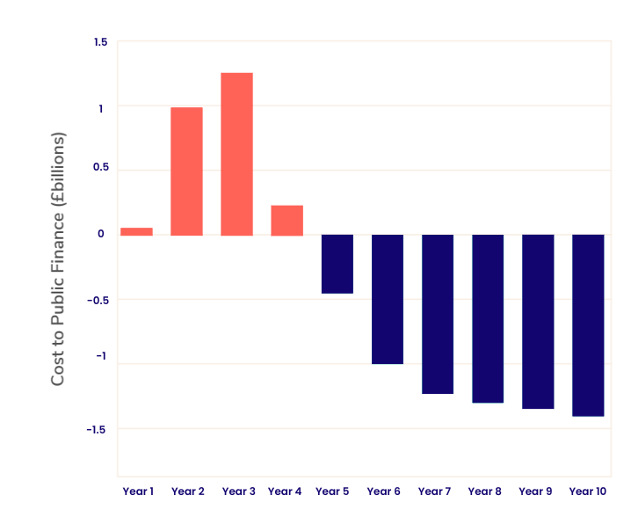

Recent long-term modelling by the UK Government shows us that providing social care for children could become cost neutral within ten years (see Figure 1). It would require a £2.6 billion investment in preventative reforms over four years – no small fee – however it would have a profound impact on the lives of children and families for decades to come.

The prevention-focused reforms include bolstered universal and community family supports (Family Hubs, school nurses, and community groups), supplemented with Multidisciplinary Family Help teams to provide more tailored support to families where needed.

Figure 1 | The 2022 UK Independent Review into Children’s Social Care found that investing in prevention-focussed reforms could be cost-neutral to the government within ten years

Sophisticated long-term modelling is not only relevant to the NSW child protection system, but also the social sector more widely. A similar approach could be applied to the benefit of preventative services across health care, youth justice, responding to domestic violence, social housing and many other priority areas for NSW.

The independent review’s modelling was a big step in the right direction, but even the compelling return on investment it laid out did not manage to convince the UK Government to invest in prevention at the scale needed – the response to the review only received £200 million of the £2.6 billion that was recommended. Our budget and political cycles are not designed to encourage or reward longer-term benefits.

How to get off the hamster wheel

A multi-pronged approach is needed to justify funding and enhance preventative services. Here are three steps policymakers could take to shift the dynamic in a more positive direction and sustainably prioritise prevention.

First, demonstrate the long-term impact through better modelling, such as that in the UK’s Independent Review. There is an opportunity to show the long-term impacts of prevention spending on government budgets and potentially open new policy windows for investment in prevention. The UK modelling tells a compelling story of avoided costs over ten years. Fortunately, NSW already has the Human Services Dataset, which modelling can be built on.

Second, create innovative investment frameworks for prevention, such as Victoria’s Early Intervention Investment Framework. While governments are required to continue funding services at the “crisis end”, they can also start ensuring that funding for prevention is protected and builds upon itself, through innovative investment approaches.

Victoria’s Early Intervention Investment Framework has two goals: (1) improve outcomes for Victorian service users through timely and effective assistance; and (2) reduce growth in government expenditure through the decline in the use of acute services. The Framework uses several innovative approaches, including a ten-year time horizon for estimating avoided costs to the government, built-in mechanisms to invest in programs that work and quickly disinvest from those that do not, and sharing avoided costs across government departments to acknowledge the inherent connections across the social services. Victoria should continue to build on this approach while other jurisdictions should innovate along similar lines.

Third, adjust budget and accounting mechanisms to consider the long-term benefits of prevention spending. Budget and accounting processes could be redesigned to capture the benefits of prevention spending. For example, each year the NSW Government hands down a budget that includes a forecast of the budget position over the “forward estimates”. The forward estimates are only four years, which limits their ability to illustrate avoided costs achieved through preventative reforms, such as those outlined in the UK Review. A longer time horizon may make it easier to justify and support this type of expenditure.

Other considerations could include revisiting the discount rate (which currently prioritises short-term benefits over potential longer-term outcomes), or introducing Preventative Departmental Expenditure Limits (PDEL) as advocated by UK-based think tank Demos. PDEL would require departments to spend a certain portion of their budget on prevention each year, with these amounts ring-fenced to ensure there is no risk of funding slipping to short-term crises or priorities.

Investing seriously in prevention will require a significant cultural shift – across government, its partners and the public – towards earlier support. Ultimately, a preventative approach is critical to government’s capacity to enable citizens to build their own capabilities and achieve greater wellbeing.

Hannah Lobb is a Manager in the Research and Policy Team at JMI. She has previously worked on health system funding, reform and strategy in Australia and New Zealand.

Image credit: Images Rouges

Features

Subscribe to The Policymaker

Explore more articles

Features

Explore more articles

Subscribe to The Policymaker