2 February 2024

Despite the dedicated efforts of many policymakers, a litany of government reviews and inquiries reveal a compliance-driven, fragmented social services system that is not working. Across employment services, aged care, settlement services, early childhood, and more, thousands of pages written across successive governments tell the story of a broken system.

These reports describe a vision for a better social services system that is responsive, accessible, easy to use, and supports people and communities to thrive – a system that works for people. But the long lists of recommendations often result in system tweaks and adjustments, focusing on the same things without ever fixing them.

A predetermined pattern of review, recommend and adjust has become the norm – a carousel that is perpetually in motion, but doesn't move the system forward. Meanwhile, disadvantage becomes entrenched and trust in government stagnates.

The abundance of technical recommendations fixate on what government does, not seeing communities as part of the solution. A focus on compliance has given rise to an “us and them” dynamic that creates distance between government and community. Until we learn how to better connect policy and service design with “the people they are meant to serve”, a system that works for people will remain out of reach.

The recent Rebuilding Employment Services report by the House Select Committee on Workforce Australia Employment Services gets to the heart of the issue: government isn’t out to get you, it’s here to support you. The recommendations lay the foundation for shifting the system from compliance to alliance. However, effectively reforming a system overwhelmed by “red tape, compliance requirements and pointless mandatory activities” will require building trust.

Unfortunately, a compliance-driven system doesn’t create much space for trust. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap emphasises place-based partnership and shared decision-making- signalling an intended shift in how government works with community. The draft review of the agreement identifies that these elements have not been adequately implemented and proposes improving accountability through enforcement. But partnership can’t be enforced – the national agreement will only come to life by growing trusting relationships.

This highlights a fundamental challenge for public servants, community leaders, service providers and other essential actors. If we want a social services system that enables individual and community wellbeing, we’re going to need to transform the relationship between government and community.

The drift into two systems

Over the years, Australia's social services have drifted into two systems. We have “big-system” national initiatives such as policy frameworks and service systems led by ministers and senior bureaucrats across Commonwealth, state and territory governments (e.g., Workforce Australia Employment Services, National Agreement on Closing the Gap). We have “small-system” local initiatives such as regional alliances and collective impact initiatives led by community leaders or government representatives at the local and regional level (e.g., Logan Together, Hunter Jobs Alliance).

Both systems aim to support thriving communities, but they often operate in silos, disconnected and misaligned. Community-level initiatives focus on trust and collaboration. Policy and service design processes can be visionary and transformative, but suffer from lacklustre implementation as business-as-usual, compliance-focused approaches stifle trust and lead to narrow services and fragmentation.

As the disconnect between both systems persists, big-system initiatives remain stuck on the carousel, while small-system initiatives work around systemic limitations and do the best they can with limited resources. Big-system policy settings and funding are out of reach for small, impactful initiatives and the innovation that takes place at a local level remains largely undiscovered.

As a result, innovative practice is not translated into transformative policy. Public servants leading these efforts do so by going against the grain, and while the big service systems may shift ever so slightly, communities hardly notice and the opportunity for an enduring joined-up approach is rarely, if ever, realised.

Getting from the What to the How

Agreement on what needs to change is commonplace, but consensus on how to make change is rare. Some actors pursue continuous tweaks within big systems for practicality, while others pursue transformative change within small systems for agility. The challenge is to integrate both systems, centring people and community, and to build a system grounded in genuine partnership.

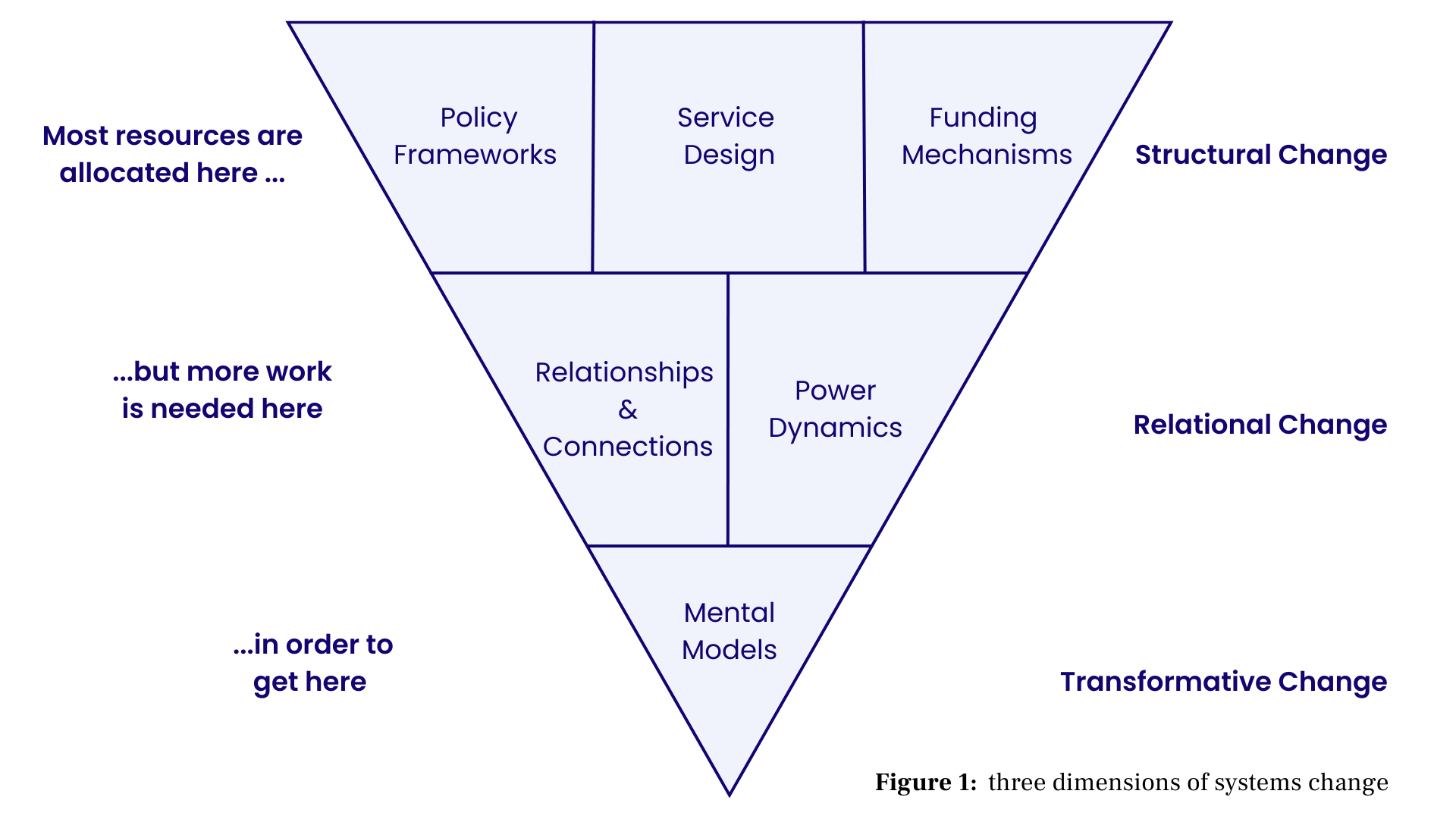

Systems change “focuses on shifting the whole rather than tinkering with minor parts,” and involves three dimensions: structural, relational and transformative (figure 1).

Our research, looking at examples in Australia and overseas, reveals how change can be operationalised across all three dimensions. These examples haven’t been limited to small-system initiatives – though we typically see greater innovation here – and include work led by government.

One example is Rhode Island’s Department of Labor and Training (DLT) who struggled to attract talented workers. Despite investing USD 14 million in a workforce development program, the department was not confident that it resulted in better outcomes for participants and did not have the information they needed to guide policy decisions. They undertook the following changes:

- Structural change: DLT modified their public administration tools to respond to their intended purpose. They re-engineered their data collection systems to capture meaningful metrics, and piloted active contract management strategies with several training programs.

- Relational change: DLT invested time in relationships, and in understanding the real-world impacts of their decision-making. They held monthly meetings with training providers to examine performance trends and solve problems in real-time. These meetings strengthened their relationship, and led to more regular and productive communication.

- Transformative change: Lessons learnt were translated into a shift in ways of working across DLT. With active contract management shown to improve service delivery, they plan to scale these practices and build the capacity of DLT’s staff to embed a collaborative approach into their performance management strategy.

While structural elements like policy frameworks, service design and funding mechanisms are important, it is the relational elements that underpin impactful implementation. Had DLT limited their role to rolling out a new data collection system, they would not have leveraged the insights of training providers and responded to changing contexts. Had the relationship between DLT and training providers remained transactional rather than collaborative, this program would not have provided the impetus for broader change in ways of working across the department.

These relational elements are commonly featured in charters and strategies, but when developed in isolation from the structural elements or without adequate input from communities and service providers, the opportunity for meaningful reform is lost.

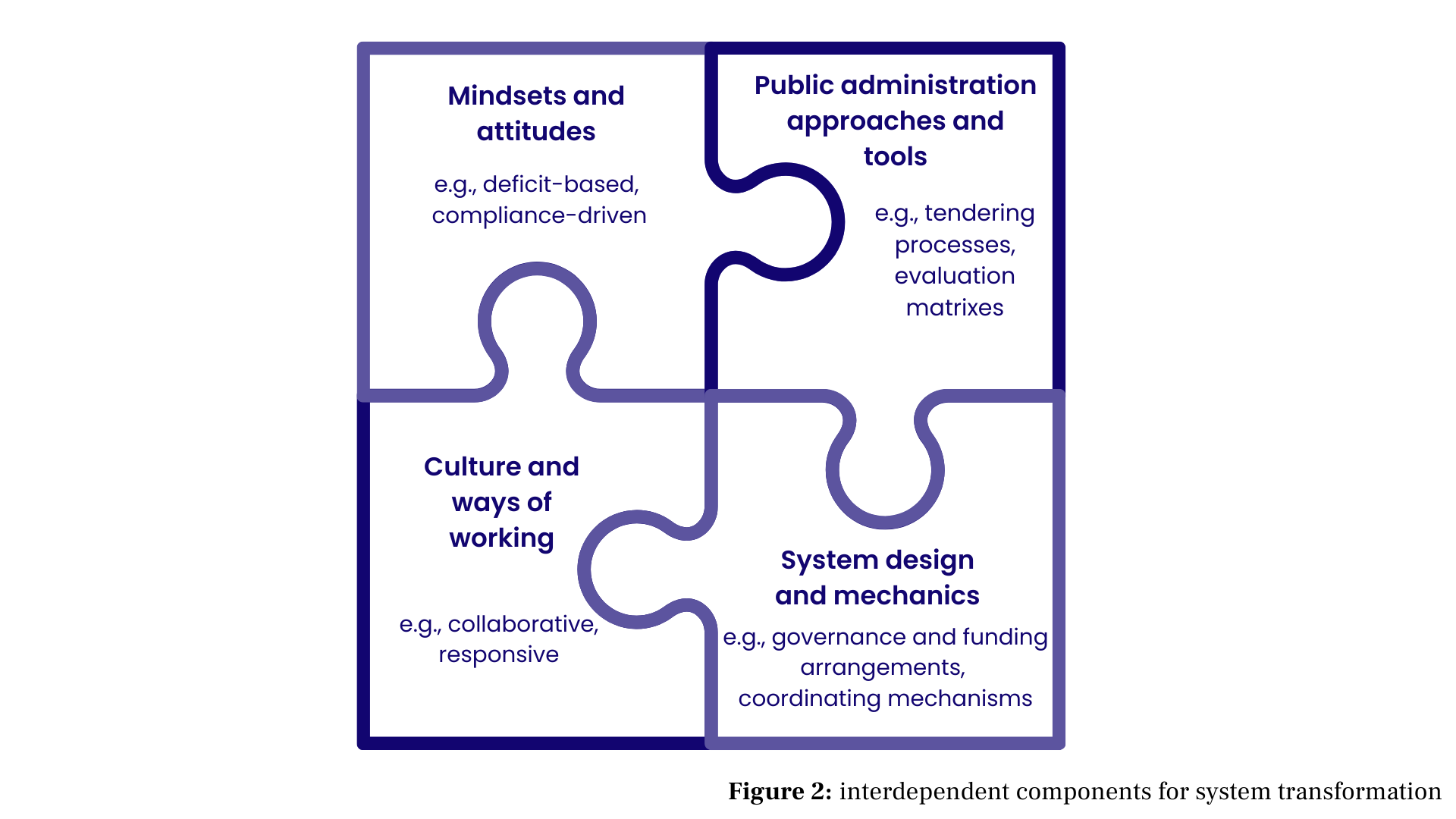

If we want to build trust, repair relationships and establish genuine partnerships, we need to shift a number of components in interconnected ways. This includes mindsets and attitudes; culture and ways of working; public administration approaches and tools; and system design and mechanics (figure 2).

A shift in mindset alone is inadequate if the tools and approaches remain unchanged, and updated tools or approaches are unlikely to be implemented at scale if the system design and ways of working are not fit for purpose. Like the DLT in Rhode Island, identifying opportunities for change within existing processes, and intentionally creating space to nurture relationships is essential.

When change is continuously pursued across all components over the long term, they ultimately lead to a transformed system where big and small systems work alongside and learn from each other to enable people and communities to thrive and flourish.

How we begin

There are a multitude of national social services system reform processes underway. There are also reforms to the Australian Public Service aimed at establishing a “genuine partnership with the community to solve problems”. We can leverage these – not just to fix the system, but to transform the relationships within it. This is a long road, but we can begin by:

- Structural change: Ensuring that policy and service design processes are clear on their intended purpose (getting people jobs, building strong communities, giving children the best start in life, etc.). We must then ensure that carefully considered and aligned policy objectives, tendering processes, governance structures and operational infrastructure flow from this clarity. Fit-for-purpose tools and mechanisms are key.

- Relational change: Challenging established power dynamics through collaborative governance models and shared decision-making processes between government and community that seek to strengthen relationships, deepen trust and create momentum around shared vision and purpose. This is the bedrock of genuine and effective partnership.

- Transformative change: Shared learning between government strategies, frameworks, toolkits and guidelines and community-level practice at local and regional levels. This ensures an ongoing interaction between policy and practice for the purpose of system improvement. Set and forget is not an option.

In his recent speech to the public service, the Secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Glyn Davis, shared a vision for a social services system “designed to build capability and resilience, focused on the whole person, grounded in community.” Tweaks and adjustments won’t make this vision a reality. It can only be achieved by getting off the carousel, bringing together the systems we have and fostering genuine partnership between government and community.

Cliff Eberly is the Director for Resilient People and Places Program at the Centre for Policy Development. He has worked on people-centred government in Australia and internationally for 18 years.

Wenqian Gan is a Policy Adviser for Resilient People and Places Program at the Centre for Policy Development. She is a qualitative researcher working at the intersection of design and social change.

Image credit: Getty Images

Features

Subscribe to The Policymaker

Explore more articles

Features

Pam Joseph, Cate Massola, Margot Rawsthorne & Amanda Howard

Susan Harris Rimmer, Ed Morgan and Sofija Tanveska

Susan Harris Rimmer, Ed Morgan and Sofija Tanveska

Explore more articles

Subscribe to The Policymaker