The Finger and the Moon: measuring research impact by nesting abstractions in contexts

Simple quantitative metrics don’t do justice to the breadth and complexity of human experience. Researchers and policymakers can benefit from frameworks implementing a nested relationship between data and lived experiences, metrics and relational processes.

7 February 2024

There is a Zen Buddhist saying, “Do not mistake the finger pointing at the moon for the moon itself.” In a world increasingly guided by metrics and data, care must be taken not to mistake those abstractions for the reality that they seek to represent.

In research and policy settings this is particularly important. What is considered “success”, how success is measured, and who decides what things like success and metrics mean – these all influence jobs, promotions, priorities, and outcomes for communities. What we need is a multi-layered approach to measuring success, based on a simple idea: nesting abstractions-in-contexts.

Background

Historically in western culture, it has been rare to be explicit and deliberate about values in research that seeks to benefit communities. The pursuit of “value-free” knowledge was foundational to modern science. Under this paradigm, disciplines have become increasingly fragmented, and many assumptions are largely unquestioned. Lived experience has not been valued in a hierarchy of knowledge that elevates quantitative data and statistics over interviews and other qualitative methods.

Scholars in interdisciplinary fields such as peace and conflict studies and process philosophy, and those using critical and participatory methodologies, have long questioned this approach, pointing out that the opposite of “values-explicit” is not “values-free”, but rather “values-implicit”. And as John Cobb Jr. observes: “when we downplay other values, the default value is money.”

In this context, monetary aims such as cost efficiency, profit maximisation and a balanced budget have been prioritised often other values such as social connectivity, wellbeing, human rights, peace, justice and environmental sustainability.

In recent years, multi-disciplinary institutes such as the Sydney Policy Lab, the Charles Perkins Centre and the James Martin Institute for Public Policy are beginning to flourish, seeking to contribute to the public good in different ways.

Universities are being challenged by societies and governments to contribute not only to knowledge, but to “help create a wiser world” – to be useful, to contribute to public good and to help address the great challenges of our time. This calls us to “un-learn” some of the norms and practices that prevent researchers from doing this, including the ways in which quantitative data and metrics have been valued over qualitative experiences, processes and actual outcomes for communities.

There is a long history of ideas at play here, which can be theorised as a tension between “static abstractions” (such as quantitative data, metrics) and “relational-processes” (such as the qualitative experiences of people and communities). The static-process framework draws on process philosophy to conceptualise these tensions in a tool to help with its application.

Static-process framework

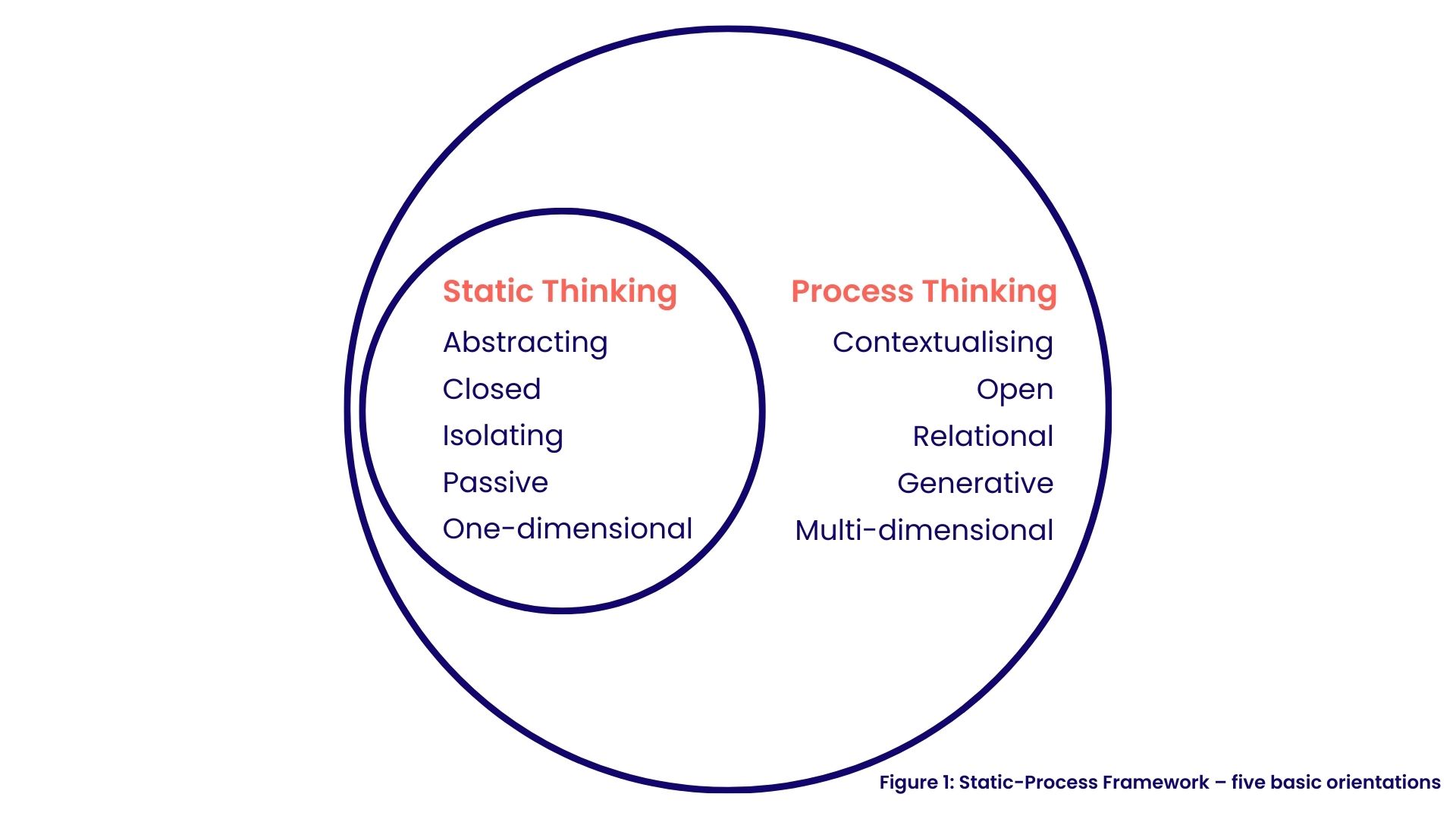

Tension between two modes of thought – “static thinking” and “process thinking” – operate in almost every area of human life and human institutions. The static-process framework identifies five “basic orientations” of these modes of thought: abstracting and contextualising; closed and open; isolating and relational; passive and generative; one-dimensional and multi-dimensional (see figure 1 below).

Each of these basic orientations are derived from the first orientation and whether something is viewed through a narrow or broadly-focused lens. Static thinking applies a narrow-focused lens, abstracting “things” from their temporal and spatial contexts and reducing them to a singular dimension (for example, capturing a desired outcome in a number such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or target inflation rate). In contrast, process thinking applies a broad lens that brings “things” into the relational and temporal contexts from which they emerge (for example, people’s experiences of economic shifts, reported happiness levels, strengthened relationships and long-term outcomes for health and environments).

Static thinking isolates, and process thinking integrates; static thinking is exclusive, process thinking is inclusive. Process thinking involves a dynamic balance between the two modes of thought, appreciating the value of both ways of thinking, taking insights from abstract static thinking and nesting them in the context of relational processes. This framework can be applied to all sorts of issues, from metaphysics and religion to economic theories. Here it is applied to research outcomes.

Research outcomes for community, policy and research

For a research or policy institute such as a university or policy lab, how is success defined? Is success having influencing policymaking and government agendas? Is success enabling people from communities to understand and build confidence in their own capacity to make policy and build influence? Is success the production of academic outputs? Or is success securing funding?

It is critical to be clear about: Success for who? Who decides? And how is it measured?

Researchers may report on successfully influencing government, but whether or not that success is linked to outcomes that communities desire takes research impact a step further.

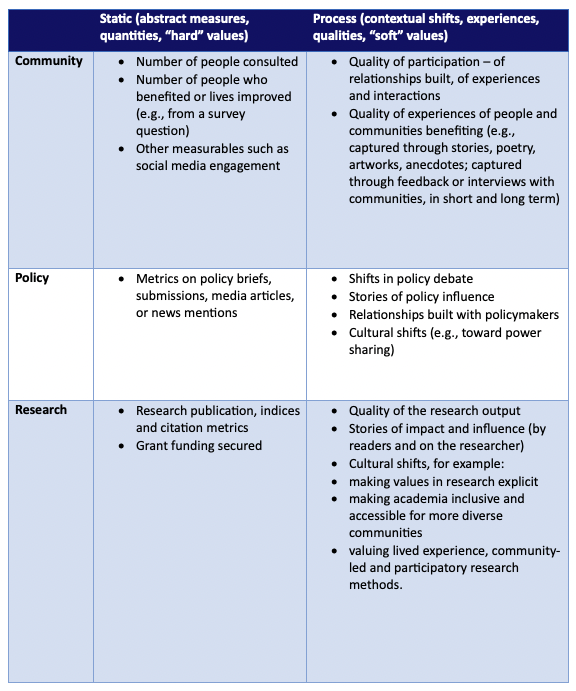

The table below applies the static-process nested approach across three domains: (1) impact for communities and improving lives; (2) impact on policymaking and government culture; and (3) impact on research and university culture.

Historically and at present, static metrics are the focus, and process contexts too elusive to capture. The proposal here, drawing on thinkers such as Julie Nelson, is not to “turn the tables” and focus only on the “process” side of the table. Instead, it is to “nest” the static within the process.

This means recognising that metrics cannot replace a detailed evaluation of a person’s research or policy impact. Metrics and insights into impact on both static and process sides of the table will never fully capture actual experiences, nor the breadth of experiences. Yet contextualising metrics, emphasising relationships and co-evaluating metrics with the people whose experiences they are intended to capture will give a better sense of successful impact.

Learning from Amy Davidson’s narrative review of Indigenous research methods, applying such a framework comes down to three core principles:

- Ask and centre community voices. Community knows what’s best for community. Respect the owners of such knowledges.

- Ensure engagements build and maintain long-term, trust-based and genuine relationships.

- Ensure these engagements benefit community in the long term and throughout the process, and in soft and hard terms (e.g., increasing capabilities, monetary payment, policy intervention). This means enabling community to have power over the decisions about their community and the way their knowledges are shared and used.

Lessons about the role of process also emerge from the Real Deal for Australia project which builds place-based responses to climate transition. Here, success is not only marked by traditional measures like engagement with political representatives, the production of research outputs or the garnering of research funds, but those outcomes are also evaluated based on the degree of community engagement in the work. The Real Deal’s relational method does not only value the production of a 40-page research report, but also values the relational processes that created it (including a listening campaign with 350 people, with 25 community leaders and five researchers supporting it).

The key across this application is nesting abstractions in experienced contexts. This means interpreting quantitative measures in qualitative contexts, with the people whose lived experiences those measurements seek to capture, or whom the policy or research is intended to benefit. Such measures and interpretations should also be held open to change, questioning assumptions and learning through the process.

In other words, do not mistake an abstraction and for what it is trying to capture: do not mistake your finger for the moon!

Dr Juliet Bennett is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Sydney Centre for Healthy Societies and Charles Perkins Centre, at the University of Sydney working on a joint research program on The Social Life of Food and Nourishment. She recently completed her PhD in peace and conflict studies, exploring the contributions of process philosophy to mitigating the climate crisis and global inequality. She is also a member of the Real Deal and a codesign community of practice.

Image credit: Getty Images

Features

Libby Hackett, Jordan Ward, Jack Isherwood, Bonnie Bley, Hannah Lobb, Isabella Whealing and Hugh Piper

Jack Isherwood and Annemie Verbeke

Katherine Kent, Liesel Spencer and Miriam Williams

Subscribe to The Policymaker

Explore more articles

Cristy Brooks, Amelia Mardon and Mike Armour

Features

Libby Hackett, Jordan Ward, Jack Isherwood, Bonnie Bley, Hannah Lobb, Isabella Whealing and Hugh Piper

Jack Isherwood and Annemie Verbeke

Katherine Kent, Liesel Spencer and Miriam Williams

Explore more articles

Cristy Brooks, Amelia Mardon and Mike Armour

Subscribe to The Policymaker