The Albanese government’s October budget presents an opportunity to transform the purpose and principles of economic policy.

On October 25, the Albanese Government will present its first Budget. Bur rather than “business as usual”, there are signs of big change on the horizon, with the Government committing to delivering Australia’s first national wellbeing budget.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers is leading the charge on a wellbeing budget. On the day he was sworn in as Treasurer, he said:

“It is really important that we measure what matters in our economy in addition to all of the traditional measures. Not instead of, but in addition to. I do want to have better ways to measure progress, and to measure the intergenerational consequences of our policies.”

A wellbeing lens has the potential to be one of the most important outcomes of this year’s Budget. But why should we have a wellbeing budget, who else does it, and do we need to be more ambitious?

Why a wellbeing budget?

A wellbeing budget is different to a traditional budget because it measures things differently. Australia’s first wellbeing budget will project not just jobs, gross domestic product (GDP), and debt, but it should also measure health and education outcomes, environmental sustainability, social inclusion, and inequality. Peter Drucker, the management expert famously said “what gets measured, gets done”. By measuring more, a wellbeing budget will be able to shine a light on where Australia needs to direct funding to improve wellbeing outcomes for all Australians. It will also highlight that our focus on GDP growth should not be the sole, or even most important, yardstick by which to measure progress.

It is with anticipation that economists and policy wonks like me hope to see Australia move beyond the mantra of “jobs and growth”. Critiques of GDP (or gross national product (GNP)) as a measure of success are not new, but they are often not part of mainstream economic discussions. Robert F. Kennedy said on the presidential campaign trail in 1968:

“Our gross national product…counts air pollution and cigarette advertising and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage… It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl.…Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play.”

Although Kennedy’s critique got little attention at the time, it has since become famous, and deservedly so, because it gives succinct voice to almost all the major criticisms of our traditional measure of economic success: GDP. While there is clearly an important place for measuring GDP, both as an established and tested source of measuring and comparing growth in an economy over time and internationally, shortcomings remain. These are what a wellbeing budget seeks to manage. Three major criticisms of GDP are: it is fundamentally a faulty measure; it takes no account of sustainability or durability; and progress and development can be better gauged with other metrics. Broadening beyond GDP as a measure of our economic success is key to a wellbeing budget.

Who else has a wellbeing policy?

Several countries have reckoned with the fact that there is more to a national economy than GDP. Governments, including New Zealand, Scotland, and closer to home in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), have incorporated wellbeing frameworks into budgeting or policy-decision making.

New Zealand’s first wellbeing budget was delivered in 2019 and is now informed by the Living Standards Framework. The Framework sits alongside three other documents – on Māori, Pacific, and children’s perspectives on wellbeing.

Extra funding has been allocated to wellbeing priorities in each of the four years. The 2022 Budget, for example, had an extra NZ$580 million (about A$518 million) for health, social and justice programs contributing to Māori wellbeing.

A sense of the long-term benefits of wellbeing measures comes from Scotland. The Scottish Government has not yet gone as far as New Zealand with a wellbeing budget, but for 15 years it has had a “well-being framework” helping to shape spending priorities.

The National Performance Framework was adopted in 2007 with a ten-year vision to measure and improve wellbeing outcomes. Updated in 2018, it covers 11 major outcomes – from “a globally competitive, entrepreneurial, inclusive and sustainable economy” to children growing up “loved, safe and respected” – with 81 measures of improvement (such as social and physical development scores as measures of child wellbeing).

Meanwhile, the ACT Government’s Wellbeing Framework comprises 12 indicators to measure Canberrans’ “personal wellbeing” and “quality of life”. Significantly, “economy” is just one of those 12 domains, alongside “environment and climate”, “social connection” and “health”.

Have wellbeing frameworks and budgets made a difference?

Wellbeing budgeting in New Zealand has focused attention on areas where wellbeing is lagging. Challenges such as child poverty, climate change, and income inequality need decades of sustained effort, not four years of the standard budgeting cycle. These are areas that have often been neglected precisely because they are difficult and need more than one election cycle to achieve outcomes.

Criticisms of the New Zealand process for not yet improving outcomes fail to appreciate the point of the reform: namely, to place greater priority on a range of measures so as to improve outcomes. It also ignores just how long real reform takes to improve wellbeing. Criticisms are doubly undeserved given the context of the past couple of years, with the challenges of COVID-19, supply chain disruptions and global inflation.

Given wellbeing frameworks are a relatively new phenomenon (with the exception of Bhutan), most of the work to date has been on what wellbeing is and how to measure it. The next step will be to start including provision for more wellbeing measurement (like a more regular time use survey) as part of our national data collection efforts.

Why Australia (and the world) needs a wellbeing economy

In one sense, wellbeing economics is simply economics. Economists have always been concerned with human wellbeing (or welfare as it has been called in the literature) and lessons about the importance of macroeconomic stability and competitive markets, for example, remain essential foundations for public policy focused on people’s wellbeing.

But there has been a tradition in the economics literature to presume that the most important contribution that the discipline can make to wellbeing is to provide knowledge on how to foster economic growth. We see this everywhere, from macroeconomic policy to development economics.

This inevitably directs policy toward measuring economic production as the primary metric of economic performance. But it is increasingly clear that people don’t view growth as the most important thing. Among G20 countries, 73 per cent of people support the idea that their country’s economic priorities broaden to include not only profit and wealth accumulation, but also to consider human wellbeing and ecological protection. This view is consistently high among all G20 countries.

There are several new economy models that countries like Australia could examine, taking on board the parts that will work for us in the near term and “stretch” goals for us to work towards in the coming decades.

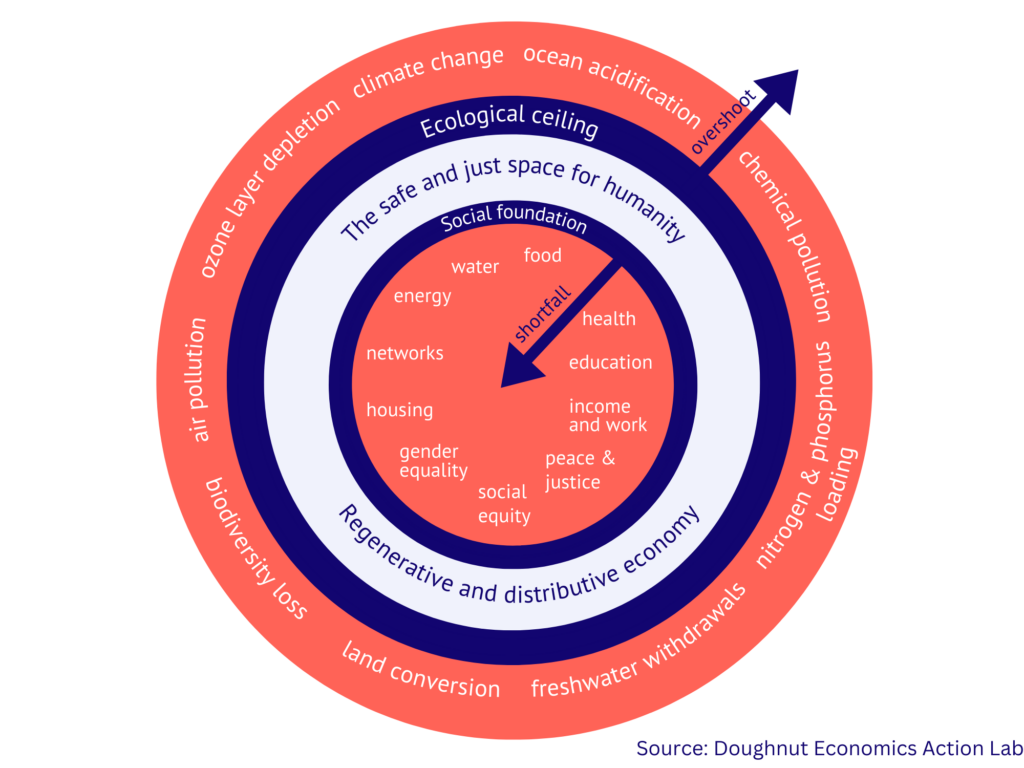

One model is doughnut economics, developed by Oxford economist Kate Raworth. Doughnut Economics proposes an economic mindset and is not a set of policies and institutions, but rather a way of thinking to bring about the regenerative and distributive dynamics we need to address the challenges of the twenty-first century. The doughnut (named for the model’s shape) would work to ensure no one falls short on life’s essentials (like income and work, social equity, and housing), while ensuring humanity does not overshoot planetary boundaries (like climate change, air pollution, and biodiversity loss).

A wellbeing budget is a great first step for Australia and an important start to a national conversation on what is important to the wellbeing of all Australians. When considering what to include in its wellbeing framework, Scottish citizens were asked “in ten years’ time, I want a Scotland which is…”. Australians of all ages, including children, should also be asked to consider this question.

Further, in Australia, we could ask citizens what is working well and what needs to change. Evidence-based policy and regular feedback from citizens is important to shape the direction of Australia’s wellbeing economy and bolster our democracy. There will be plenty of sceptics, but wellbeing budgets are far from radical. Yes, they are still new and being tested, but that is a key reason Australia should be ambitious and a world leader (rather than the laggard we have been derided for on climate). Australia once led the world in public financial management, from its adoption of intergenerational reports, accrual accounting, performance budgeting and, though waveringly, gender budgeting in past decades.

It is also great opportunity for Australia to talk about wellbeing economics in international forums. Alongside a G7 or G20, Australia could propose a Wellbeing 7 (W7) or W20: a group of nations who are committed to transforming their economies beyond GDP to focus on wellbeing of people and planet. Such a grouping could include the likes of New Zealand, Scotland, the Netherlands, Bhutan, Wales, and Finland.

Bold economic leadership and transformation will ensure Australians thrive in the 21st century. The October 2022 Budget could be just the beginning.

Dr Alicia Mollaun is the Senior Manager for Economic Policy at Equity Economics and Development Partners, a firm committed developing solutions to complex challenges domestically and internationally through more inclusive growth. Alicia has previously worked at the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and in the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, the Hon. Julia Gillard, MP. Alicia has a PhD in Public Policy from the Crawford School at the Australian National University.