Digital technologies offer an opportunity to tackle Australia’s youth mental health crisis. But effective solutions will require us to think innovatively and listen to the voices of young people with first-hand experience.

Youth mental health is at a crisis point. Poor mental health is affecting nearly half of Australia’s young population; almost 40 per cent of 16 to 24 year olds reported a mental health disorder in 2020-2021. COVID-19 infections amongst young people pale in comparison (recorded cases only implicate 23 per cent of 10 to 30 year olds). Despite the mental health epidemic’s alarming scale, leaders have failed to respond with policy that effectively addresses the needs of young people.

There are several service gaps currently leaving young people vulnerable. Waiting times for psychologists are at an all-time high and, as more young people than ever are seeking professional help, the demand for support continues to far outweigh the supply. Transparent information surrounding psychological services and their availability is also lacking. Moreover, a lack of communication between health specialists, for instance general practitioners (GPs) and psychologists, means that young people often receive inappropriate treatment, leading to poor functional outcomes and despondency towards professional support options. Digital technologies offer the opportunity to address these service gaps and engender systems-reform to make mental health care more accessible for young people. The role of these technologies will be to complement high-quality professional care, while also alleviating the current burden on clinicians by making processes more efficient.

What are digital technologies?

“Digital technologies” is a broad term encompassing electronic tools, systems, devices and resources that generate, store or process data. Examples in the mental health space include smartphone apps (e.g., Headspace), online treatment programs (e.g., This Way Up) and smart technologies that track wellbeing (e.g., Beyond Now app). The advantage of digital technologies is that they are accessible to everyone who owns a smartphone (over 95 per cent of young Australians in 2022). They also tend to be far more appealing to younger generations whose high digital literacy allows them to easily navigate and integrate new technologies into their daily lives.

How can technology be part of the solution?

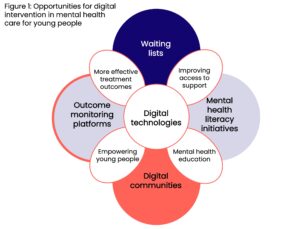

The pandemic demonstrated how rapidly new technologies can be built when innovative thinking is backed by the right funding. The same progressive thinking used to create digital solutions to the COVID crisis can (and should) be applied to solve current issues in mental health care. Here are four ways that digital technologies can improve Australia’s youth mental health crisis (figure 1).

Waiting lists

Funding should focus on the creation of digital waitlist platforms that track psychologists’ wait times and allow those seeking support to join a waitlist. Lists should be implemented according to local regions and stratified by speciality so that clients can be effectively triaged according to individual psychological needs. The United Kingdom has recently implemented this type of centralised system, creating an NHS mental health waiting list that guarantees patients will be seen by a professional within 18 weeks of registering. In Australia, this could be operationalised as a smart phone app where clinicians register their areas of speciality, pricing and current waiting lists. This would allow young people (and their carers) to easily search for a local specialist, view or join their waitlist, and be notified of any openings or cancellations that come up.

The kind of transparency provided by waiting lists will allow young people to seek alternative support options while they wait for the right professional. This platform would also dramatically improve the efficiency of the current referral system and offer a lifeline to struggling GPs who are often at a loss about where to send young people presenting with mental health concerns.

Mental health literacy initiatives

Most young Australians do not have the clinical awareness to understand their mental health, nor the health-systems literacy to navigate the healthcare system. Policy in this area should focus on developing digital mental health literacy resources that teach emotional awareness and healthy support-seeking behaviours. The “Transitions” program in Canada offers one effective example of how digital booklets can be provided to young people to improve mental health literacy and skills in seeking out support. In Finland, this program has been digitised to include lectures from mental health professionals and web-based learning modules given to students as part of their orientation to university.

In Australia, such initiatives must also teach health-systems literacy, which means clearly explaining the practical processes required to receive mental health care. For instance, how to receive a mental health care plan. We do not teach young people to drive without first teaching the road rules—and we should not be teaching emotional literacy without the skills to navigate relevant healthcare processes.

(Digital) communities

To address the underlying factors of social isolation and loneliness driving mental health issues in young people, policy needs to focus on building strong communities for young people. As professional support continues to be inaccessible for most, online communities offer young people an alternative support network where they can build social connections and develop valuable peer-support systems. While they are hosted on digital platforms, these communities facilitate in-person connections, while also giving young people the autonomy to discuss mental health concerns in a safe space driven by shared knowledge and support.

Young entrepreneurs are already building these digital communities around Australia. One recent example includes Uni-Link, a new digital platform that connects university students with shared interests (like the original Facebook platform). However, most of the funding for these projects comes from the private sector, including venture capital, who tend to prioritise returns on investment over quality control (only 3 per cent of mental health apps are evidence based). Governments should therefore create funding opportunities for high-quality initiatives that challenge young entrepreneurs to engage with research institutions and health professionals. Providing further resources, such as legal advice, will also help young innovators adhere to ethical and legal guidelines to create more sustainable, lower-risk products in the wellbeing sector.

Outcome Monitoring Platforms

One of the biggest opportunities offered by digital technologies is the ability to track outcomes of psychological treatments and tailor them to be more effective for young people. Digital platforms like Innowell are addressing this opportunity as they allow clients to track their symptoms, feeding this data back to their clinicians who can then tailor treatments accordingly. These platforms also allow for integrated health care, as the client’s entire health team (e.g., their GP, psychologist, and various other specialists) can access the platform to deliver holistic care that enables better functional outcomes.

Future iterations of these platforms need to be made more inclusive for young people from different cultural backgrounds, who may experience additional mental health stressors and have limited access to support. Funding the implementation of these platforms in regional communities will also be crucial, as mental health support remains virtually non-existent for young people in more remote areas. Finally, the implementation of digital platforms needs to accompany digital literacy initiatives that teach clinicians how to incorporate these new technologies into clinical practice. Resistance to change continues to be a huge challenge amongst health professionals and empowering clinicians to navigate digital solutions will be critical to ensuring the sustainability of these platforms.

Despite their potential for positive impact, funding for digital technologies should not be considered a replacement for investments in training mental health professionals and traditional psychological interventions. Caution must also be exercised in the development and implementation of these technologies, where careful consideration should be given to privacy concerns and ethical data usage. Bearing these limitations in mind, Australia’s wellbeing policy needs to be more progressive and enable the development of innovative technologies that deliver real outcomes for young people. Funding these innovative initiatives should be a top priority for the Commonwealth Government in October’s “wellbeing budget”.

Amira Skeggs is a researcher at the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre and the founder of Kindred, a not-for-profit social enterprise creating digital mental health resources for young people. She has worked across several mental health organisations and currently sits on the Raise Foundation’s Youth Advisory Council, where her work is focused on elevating young people’s voices to create more inclusive mental health initiatives. Amira graduated with first class honours and the university medal in Psychology from the University of Sydney.

Image credit: Alessandro Biascioli