15 January 2024

The flow of credit is fundamental to the health and prosperity of the real economy. Mismatch between the investment horizons and risk tolerance of borrowers and savers (and investors) can result in insufficient funding for key sectors of the economy. This is a particular challenge for sectors characterised by investments which require novel technology and long-term funding. Examples include expenditure on research and development (especially basic research), start-up companies, corporate transformations (seeking to pivot competitive advantage) and decarbonisation.

An absence of private sector capital to fund many of these initiatives has resulted in significant government assistance globally in the form of state-backed loans, tax breaks, subsidies and trade barriers. Building new industries, or transforming an economy to move up the economic value chain, is a prolonged and capital-intensive process. Success amongst east Asian economies such as South Korea, Japan and Taiwan would not have come about without sustained government funding and support (for instance, Taiwan’s semi-conductor industry is the product of investment over four decades). Australia has performed particularly poorly on this front, ranking last amongst OECD countries for economic complexity and trailing other wealthy economies on R&D spend as a share of gross domestic product.

We are currently in the midst of a new investment juncture as we seek to decarbonise the global economy over the next two to three decades. The scale of investment required will not only exceed the capacity of many private funding sources – both capital markets and banks – but the pay back horizons on much of the expenditure will surpass the risk tolerance of lenders.

Battery development is an excellent example. The Australian Government is currently seeking to capture more downstream value from critical minerals such as lithium, copper and nickel. This ranges from refining raw materials to produce ingredients and compounds for battery manufacture, right through to development and manufacture of new battery technology. Moving up the value chain to develop new onshore battery technology and production likely has a positive net present value. Unfortunately, the illiquid nature and uncertainty of future cash flows makes it an unattractive proposition to many lenders.

Even much smaller investments, for example the purchase of a new zero-emission bus fleet, has high upfront expenditures that are only recouped through long-term operational savings. Unlike a mortgage, long-term investments that lift business capability are often not backed by a valuable fixed asset, but are instead heavily reliant on the generation of future cash flows from the investment.

The promise of long-term asset funds to drive innovation

Underinvestment in innovative parts of the economy with the potential to generate significant future windfalls will result in weaker economic and productivity growth. This makes it vital that funding for long-term illiquid investments is unlocked.

The United Kingdom has responded to this challenge with the Bank of England (Financial Policy Committee), Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and Investment Association supporting the creation of FCA-approved long-term asset funds (LTAF). These open-ended funds are designed to enable investment in long-term illiquid assets such as venture capital, private equity, private debt, real estate and infrastructure. There is an expectation that LTAFs will invest at least 50 per cent of their funds in unlisted assets.

By matching investors with long-term investment horizons and appropriate risk absorption capacity with productive opportunities, LTAFs unleash a valuable new stream of capital to support economic growth and decarbonisation. They also provide an opportunity for “patient capital” to receive superior returns. Private equity and venture capital have outperformed listed equity over the past fifty years. Unlike many open-ended funds (pooled funds which allow ongoing contributions and withdrawals from investors), LTAFs have a minimum of ninety days (but can be 6 or more months) to meet withdrawal requests. This provides sufficient time for fund managers to sell illiquid unlisted assets and rebalance their portfolios in an orderly manner. Historically, there has been a mismatch between the ability of investors to withdraw funds (fast) and the speed fund managers can sell assets (slow). This has caused funds to collapse, such as the United Kingdom based Woodford Equity Income Fund, and discourages fund managers from exposing themselves to illiquid long-term investments.

LTAFs are particularly suited to defined contribution schemes (DCS) and provide a vehicle in which these funds can invest effectively in long-term illiquid assets. A DCS has an extended investment outlook, making it an excellent and large source of “patient funding”. Australia is exceptionally placed to take advantage of LTAFs due to the nation’s $3.3 trillion superannuation industry which has outgrown the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) and is in the process of increasing investment in global and unlisted assets. By contrast the United Kingdom’s DCS assets are projected to reach only £1.2 trillion by 2035 despite the United Kingdom having over twice Australia’s population.

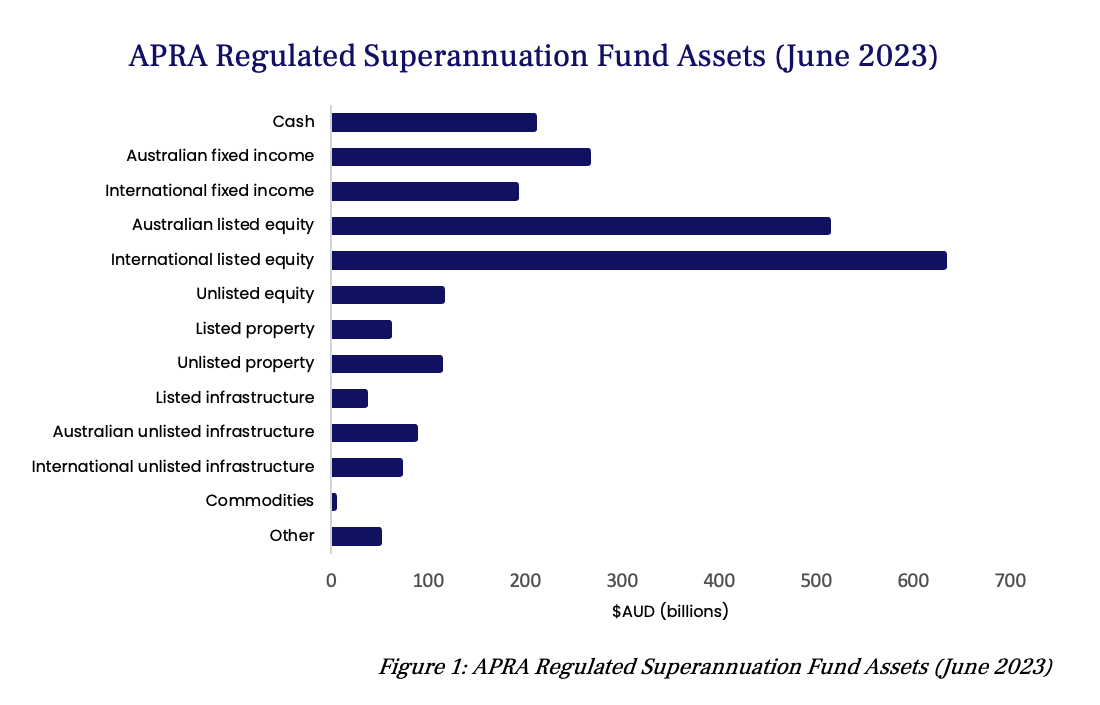

Whilst Australian superannuation funds already invest over 15 per cent of their funds in unlisted assets, about 70 per cent of these investments are in infrastructure and property (see Figure 1). This leaves significant scope for growth in investments which focus on venture capital and private equity such as the CSIRO’s “Main Sequence” fund which uses a network of experts to transform science into new companies. Without action, Australia risks losing capital overseas. For example, two major funds recently pledged $29 billion for the UK and Europe at Britain’s Global Investment Summit.

Implementing LTAFs in Australia

Commonwealth Treasurer Jim Chalmers has flagged a desire to unlock capital held within superannuation funds by broadening their purpose to deliver income for a dignified retirement in an “equitable and sustainable way”. LTAFs provide a tool to achieve this by creating a vehicle for superannuation funds to invest in long-term illiquid assets without obfuscating their core mandate of delivering for member’s retirements. Notwithstanding, success with LTAFs requires cultivation of an environment which supports long-term investment. This means having the correct regulatory frameworks (authorisation of fund types which allow investment in illiquid long-term assets) paired with coordination between government, investors, investment managers, banks and research organisations. This model has been effectively achieved in Nordic countries where pension funds, many state-owned, are major investors in unlisted assets including venture capital funds.

Successful long-term investment requires effective evaluation methodologies capable of appraising complex businesses and technologies. These need to be cultivated within major superannuation funds and specialist venture funds by drawing on templates such as CSIRO’s Main Sequence fund which houses the capability to identify research with strong commercialisation potential. Determining which investments and businesses LTAFs should support is difficult and would benefit from expertise across stakeholders to couple competence with capital. Investors want the best ventures in their portfolios. Achieving this requires technical expertise to separate spin from achievable science and business acumen to identify companies that have sound commercial models. It is collaboration of this nature which will increase the likelihood that the most promising ideas are funded and investments deliver on the bottom line.

With Australian productivity at historic lows and the economy in the midst of a major structural adjustment away from fossil fuels, policy tools which can promote capital deepening, research and development, onshore commercialisation and enhanced capability are invaluable. This will generate the high value exports and jobs that drive future prosperity by increasing growth in a sustainable manner. LTAFs are a tremendous opportunity to transform economies and accelerate decarbonisation provided they have the management framework in place to achieve sustainable returns on capital.

Christopher Day is passionate about lifting Australia’s economic complexity by better harnessing our research and resources to capture a greater share of global value chains. He has advised on the development of innovation and industrial policies in the United Kingdom, United States and Australia. Chris completed his PhD in industrial strategy with the Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, University of Sydney, having graduated with an MPhil from Cambridge and university medal from UTS.

Image credit: Getty Images

Features

Simon Rowell

Teddy Nagaddya, Jenna Condie, Sharlotte Tusasiirwe & Kate Huppatz

Subscribe to The Policymaker

Explore more articles

Teddy Nagaddya, Jenna Condie, Sharlotte Tusasiirwe & Kate Huppatz

Ehsan Noroozinejad Farsangi & Hassan Gholipour Fereidouni

Features

Simon Rowell

Teddy Nagaddya, Jenna Condie, Sharlotte Tusasiirwe & Kate Huppatz

Explore more articles

Teddy Nagaddya, Jenna Condie, Sharlotte Tusasiirwe & Kate Huppatz

Ehsan Noroozinejad Farsangi & Hassan Gholipour Fereidouni

Subscribe to The Policymaker