18 September 2023

Legalising cocaine is a solution to NSW’s recent spate of gang-related shootings, according to NSW Greens MP Cate Faehrmann. The suggestion builds on what could be called a grassroots policy proposal by an unnamed police officer who quipped, “These gangsters will be on Centrelink in six months if you legalised [drugs]”.

While currently a far from popular view among politicians, police, or even the general public, these comments tap into a fundamental problem for governments wanting to better manage the drug problem, and the substantial harms that occur with a black market and illicit drug supply. If legalisation is a potential answer, what might that look like? Here we explore some of the considerations within a suite of legalisation options, with the goal of improving the quality of the debate around this polarising policy option.

The legal supply of drugs can be a scary prospect. That is, until you realise that this is the situation for two commonly used drugs – alcohol and tobacco. These drugs are legal but subject to regulations and supply controls (such as age requirements for purchase, licensing of retailers and advertising restrictions). And for other drugs, such as some opioids (e.g., morphine, codeine) and benzodiazepines, legal access occurs via prescription from a doctor, and supply via registered pharmacists. In many countries, including Australia, cannabis is also regulated for medicinal use.

So, how might drugs like cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, cannabis and ecstasy be regulated under a legalised framework? Legalisation can often get flattened to simply being “not prohibition” and as a result assumed to be an entirely free market. Yet numerous legalisation options exist.

There are now many relevant international examples and publications that help define the regulatory mechanisms available to government and engage the public in considering alternatives. While each drug might have a different regulatory system, all must consider similar factors such as production, profit, product types, potency and price to name a few (see Beau Kilmer’s helpful “14Ps” for other considerations).

Discussions and debate would be enhanced if three different dimensions to legalisation are considered: supply arrangements, retail arrangements and consumption arrangements.

Supply arrangements

The supply arrangements – or where, how and by whom drugs are produced – could be configured in several different ways. Any individual or company could be permitted to supply drugs. The Greens tabled a bill in federal parliament recently which proposes a system for registration of cannabis strains and licencing for activities such as production and sale (through the establishment of the “Cannabis Australia National Agency”).

Many experts worry about a for-profit supply industry – with vested interests in ensuring maximum consumption. A not-for-profit supplier arrangement would obviate those concerns. For cannabis, the cannabis social club is one model of not-for-profit supply. Another not-for-profit supplier might be the government. Historically, alcohol has been a government-owned monopoly in some countries.

Whether not-for-profit or for-profit suppliers, there are many regulatory tools to manage supply arrangements. There might be specific requirements about the product, including allowable purity levels, the quality standards of manufacturing and allowable production limits.

For drugs that can be home-grown, like cannabis, there are non-commercial supply arrangements. These include home-growing for personal consumption (as occurs currently in the ACT).

The supply arrangements for synthetic drugs, such as crystal methamphetamine (“ice”) and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA/Ecstasy), conjure ideas of “meth labs”. Under a legalised supply arrangement, these synthetic drugs could be produced under regulations that apply to manufacturers of medicinal products.

Retail arrangements

Retail arrangements consider how people purchase drugs. There are several potential retail arrangements. One approach is through medical prescriptions whereby only registered pharmacists could sell the drug and only people with a valid prescription are able to buy it. A less restrictive model would see drugs available for sale as over-the-counter products but confined to pharmacies (as is the case now with stronger cold and flu tablets).

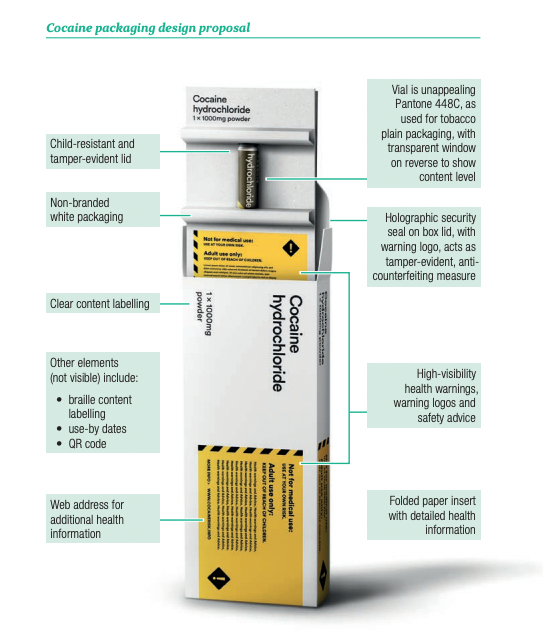

“Cocaine packaging design proposal”. Source: Transform Drug Policy Foundation, How to regulate stimulants: a practical guide (2020), p. 66. Design: Halo Media. CC BY-NC-SA

A third retail option is dedicated stores (which may include not-for-profit sales, especially if linked to a government supply arrangement). Versions of this occur in cannabis “head shops” (similar to tobacconists) in the United States, Canada, Thailand and Malta. In more familiar terms, dedicated stores to sell drugs could parallel Australia’s current off-license (take-away) liquor outlet arrangements.

Aside from off-license retailers, on-license retailers could also be considered. This could take a similar form to alcohol where venues are licenced for consumption at the premises (e.g., pubs, bars, clubs and restaurants), with associated license conditions.

The most liberal model would be a free market whereby anyone is permitted to sell drugs. While regulations in this model would be thin, there would still be some basic standards such as truth in advertising and safety (i.e., purity) standards.

All of these retail options can include regulation around the price to be paid (including specifying a minimum unit price, and rates of taxation), the amount purchased (including potential limits on single-occasion quantity purchased), advertising restrictions and restrictions on hours of sale.

All retail options come with challenges. Medical models (prescription, over-the-counter) will need to consider how this approach medicalises what for many people is recreational. For some, the restrictions on access that this affords may be an important goal; for others, heavy restrictions on access would likely not curtail the black market, meaning alternative access settings may be preferable.

On the other end of the spectrum, experiences with the alcohol and tobacco industries suggest that adding regulations (e.g., introducing stricter advertising and sale restrictions) is more difficult once industry and lobby groups are established and financed. Funnily enough, the old adage heard in both medical and recreational contexts may be good advice for any retail approach: “start low, go slow.”

Consumption arrangements

There are several possible regulations around consumption. While not a given, it is hard to imagine any system of legal regulation that does not include age restrictions for consumption. These could be set at similar levels for different substances (e.g., 18 years) or have some substances restricted to older adults (e.g., 21 years).

Other consumer arrangements could include supervised consumption sites, as well as bans or restrictions on public consumption (particularly relevant for some routes of administration such as inhalation (i.e., smoking) or injecting drug use). Bans on public consumption can also be defined by place, for example within 500 metres of schools and similar.

The extent of consumption – whether population prevalence or amount consumed per occasion – is also linked to retail regulations, including product labelling (e.g., health and risk information), advertising, product types, potency and price.

Preventing consumption by young people and managing harmful consumption will require resource allocation. This may include targeted media and education campaigns that provide realistic information about use and harms, as well as investment in harm reduction measures and treatment services.

Towards a better-informed debate

The legalisation of currently illicit drugs is invoked by advocates as a means to address a host of substantial issues present under the status quo: a thriving black market, unregulated and untaxed supply, dangerous purity and potency variations, uneven policing practices, and high law enforcement time and costs.

Debates around legalisation need to consider the various models and design considerations, as well as the political, social and cultural feasibility of each scenario. Doing so requires a clear-eyed acceptance of the complexity of the issue and realities of drug use. Drugs can be harmful – and there is a strong relationship between availability and rates of consumption. Harms exist beyond the qualities of a substance itself and the elimination of black markets is not inevitable with legalisation (for instance, there remain cannabis black markets in places where legalisation has occurred).

The regulatory challenges under legalisation include considering how various legalised, regulated models address harms: harms from the black market and harms from consumption. Much debate is required to get the policy settings right, for example, making legal sales widely enough available to compete with the black market but setting the price sufficiently high to avoid attracting new consumers. These are significant regulatory challenges that require debate. The debate could be enriched with meaningful engagement of people who use drugs, whose views regarding legalised models are not homogenous, and with consideration of the multiple possible supply, retail and consumption arrangements. Getting the policy settings right will be a balancing act.

Dr Paul Kelaita is a postdoctoral fellow with the Drug Policy Modelling Program at UNSW, Sydney.

Professor Alison Ritter AO is Director of the Drug Policy Modelling Program at UNSW, Sydney. She conducts research on drug laws, drug treatment, models and methods of participation in drug policy, and research focussed on policy process. She is Editor in Chief for the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Image credit: Budding/Unsplash

Features

Subscribe to The Policymaker

Explore more articles

Features

Jack Wilson, Emily Stockings, and Maree Teesson

Jack Wilson, Emily Stockings, and Maree Teesson

Anna Skarbek and Joshua Danahay

Explore more articles

Subscribe to The Policymaker