Australia’s material footprint per capita is rising. But with the right policies, we can break the nexus between depleting our ecological resources and improving economic growth.

Nature by itself is a circular economy – its wastes are reabsorbed back into the environment for productive reuse. However, the disproportionate global growth in waste, and the rapid proliferation of inorganic waste that is difficult to break down, is entirely an anthropogenic problem. Left unaddressed, this is creating cumulative impacts on our biodiversity, food security and way of living.

Depleting natural resources at current rates is unsustainable

We are seeing an unprecedented rise in the consumption of primary materials – farmed, mined, harvested or extracted from the natural environment in other ways – which are not being replenished fast enough to sustain this level of human consumption.

Each year, Earth Overshoot Days are getting progressively earlier, indicating intensified consumption activity. By Global Footprint Network estimates, it would take the biocapacity of 4.5 earths if the world’s population lived like Australia. Only six other countries in the world currently have bigger demand for ecological resources per capita than Australia.

Our consumption and production patterns based on the linear economy approach of “take, make and dispose” are creating more and new types of wastes. At the same time, insufficient prior investment in better solutions means that resource recovery rates are not growing sufficiently quickly to keep up.

Australia is a world-leading consumer of raw materials (at over 40 tonnes per capita in 2019) and has a material footprint of 47 tonnes per capita to service final demand. Both metrics are around double the OECD benchmark. At the same time, Australia’s resources productivity is low, generating economic output of USD 1.18 for every kilogram of material consumed: less than half the OECD benchmark in 2019.

In 2020, the European Union’s second Circular Economy Action Plan highlighted the need for the EU to keep its “resource consumption within planetary boundaries”, given that global consumption of materials is expected to double in the next 40 years, and waste generation increase by 70 per cent by 2050. Resource extraction and processing alone will account for half of total greenhouse gas emissions, and over 90 per cent of biodiversity loss and water stress.

Which countries are leading the world in resource productivity?

A circular economy is one where economic growth is successfully decoupled from material use.

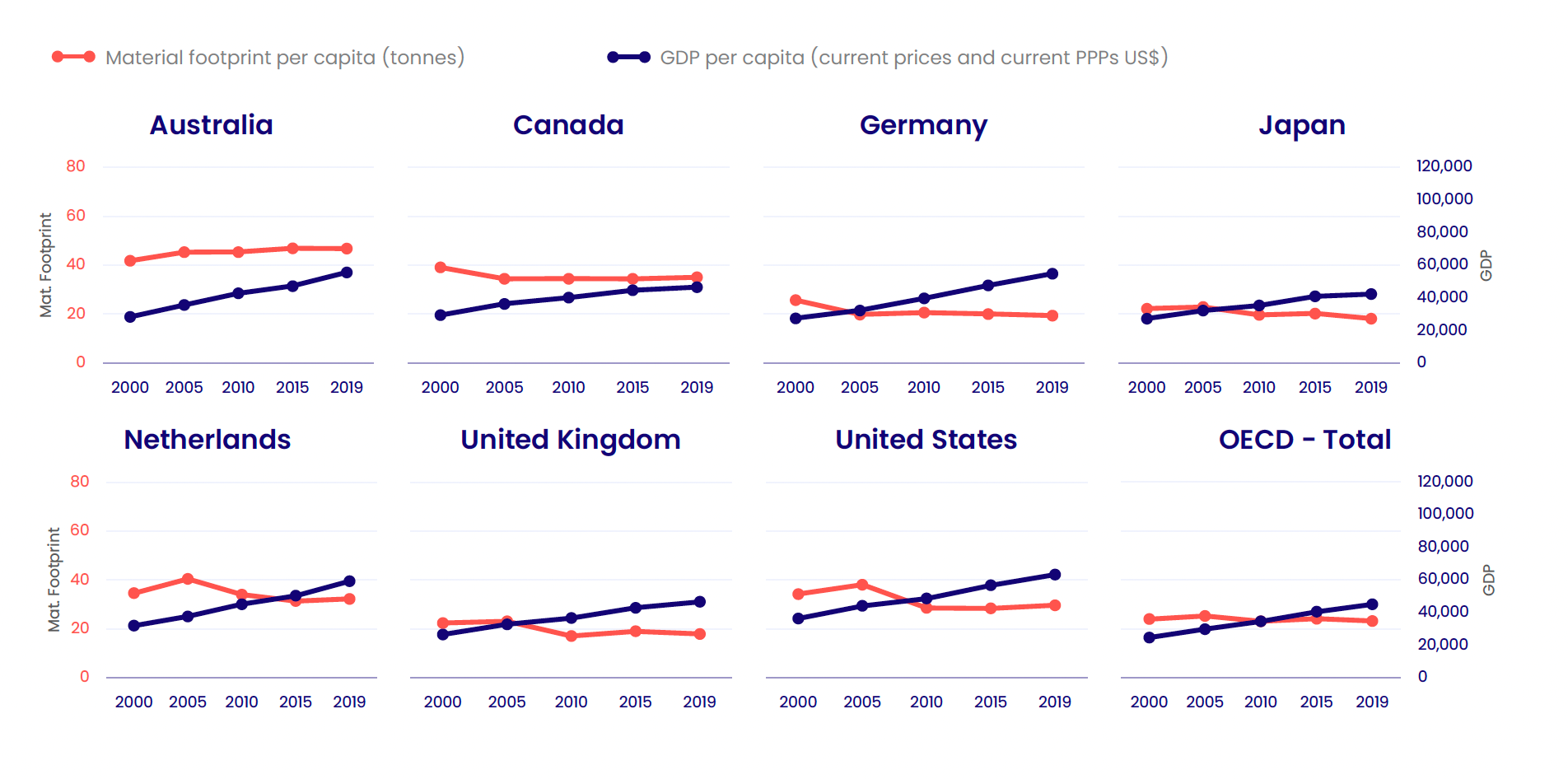

An analysis of OECD nations’ material footprints demonstrates the slow rate of progress towards decoupling, even in many high-income economies. The “material footprint” represents the total volume of raw materials needed to satisfy the final demand of an economy. This includes not just the raw materials used domestically, but also upstream raw materials used overseas in producing the finished or semi-finished goods that are used by an economy.

NSW Circular’s analysis reveals four groups of countries at different stages of progress towards a circular economy (Figure 1 shows a selection of these countries).

Leaders: This group comprises Japan and advanced European economies including Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland. They have managed to steadily reduce their material footprint per capita while increasing economic growth (absolute decoupling) and continue to progress in this direction.

Progressing: These economies are generally tracking in the right direction in terms of decoupling, although momentum in reducing their material footprint per capita has decelerated in recent years. Within the OECD, this group comprises Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Slovak Republic and Sweden.

Losing momentum: This mix of large and small economies have seen some progress in decoupling in the early 2000s to 2010s, but this momentum has stalled or even reversed in recent years. Within the OECD, this group comprises Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Laggards: These countries have seen their material footprints per capita steadily rising (albeit at a slower rate than economic growth, i.e., relative decoupling), and have shown no real progress in reducing their material footprints per capita since 2000. In the OECD, this group comprises Australia, Chile, Colombia, Estonia, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, New Zealand, Poland and Turkey.

Policy options for a more sustainable model of material use

How do we break this nexus between depleting our ecological resources, while improving economic growth and standards of living? Here are some policy solutions:

- Set goals for sustainable material use, with an action plan that includes measuring and setting targets for reducing our material footprint. Australia presently has a range of policy strategies that target different aspects of our material consumption and disposal. These range from the National Waste Action Plan (and similar strategies by the states and territories), to various infrastructure, manufacturing, and innovation programs that include the circular economy and new materials as priority sectors for development.A holistic national circular economy action plan is needed: one that goes beyond waste and recycling targets to consider all parts of the materials supply chain contributing to our consumption activity, with a view to reducing our material footprint. For example, the European Parliament has called on the European Commission to propose science-based binding EU targets for 2030 to significantly reduce the EU’s material and consumption footprints, and bring them within planetary boundaries by 2050. Independent researchers have even suggested, for example, a target cap on household resource use based on their material footprint, such as in this study from Finland. For Australia, a first step towards such a national action plan could be for governments to embed metrics to track our consumption and material footprints, and resource productivity and sufficiency, into policy frameworks to monitor progress and inform implementation. State and territory governments could also consider planning guidelines to maximise industrial symbiosis, such as those incorporated into EU law in 2018 with member states required to promote replicable practices.

- Incentives to maximise material reuse. Waste levies and product stewardship schemes, including container deposit schemes, are currently the main policy tools with financial levers for reducing waste across Australian states and territories. These are effective to a point, but by themselves are not going to be enough to reach government waste reduction targets.Further incentives should be considered for households and businesses to reuse, repair or repurpose goods. These may take the form of business incentives for repair shops, concessions for customers using these services, incentives to transition from disposable to reusable materials, and requiring design standards and labelling to facilitate repair and recycling. As a start, the government should implement the Productivity Commission’s Right to Repair report recommendations from 2021 as soon as practicable. Other policy options could include banning unnecessary waste, such as the destruction or disposal of unsold durable goods. Clothing and household goods, for example, typically have a high environmental footprint in their manufacture, are often not easily recycled, and can be donated for reuse, resold, repurposed or recycled. Similar bans have already been introduced in France and are being considered in the EU and Scotland.

- Set targets for low-carbon materials or material reuse in publicly funded infrastructure projects where feasible to slow material supply risks. Australia is projected to spend AUD 1.5 trillion in infrastructure development up to 2040. Infrastructure Australia estimates that investment in major public infrastructure over the next five years alone will exceed AUD 218 billion. This presents a significant opportunity to deploy more sustainable low-carbon materials – including recovered materials – into constructing buildings, roads, landscaping, and fit-out materials, among others. This need to slow the depletion of natural resources and shore up materials supply chain resilience is urgent. Demand for materials is expected to rise by 120 per cent over the next three years. Significant supply risks are expected from increased demand for quarried materials such as rock and bluestone (240 per cent), steel (160 per cent) and concrete (110 per cent). Beyond ramping up efforts to recover all reusable demolition waste generated through development projects, governments at all levels will also need to work with industry and groups such as the Materials and Embodied Carbon Leaders’ Alliance to find new solutions to drive reductions in embodied carbon in the built environment.

- Industry development policy to accelerate the supply and take-up of sustainable and low-carbon products. We need more sustainable products to reduce our material footprint. At the same time, we need to develop market depth and innovation to create commercially self-sustaining markets for these emerging products.Currently, Australia’s federal manufacturing policy is based on six sector-specific roadmaps. Of these, two focus on improving our use of natural resources and materials: resources technology and critical minerals processing, and recycling and clean energy. A more holistic version of this approach is needed in a sustainable product policy framework that connects research and industry policy with the material productivity targets. This framework must cover all stages of product development, including product design as it can determine more than 80 per cent of a product’s environmental impact over its lifecycle. The European Commission’s recent proposal to introduce Ecodesign for Sustainable Products regulation (repealing their 2009 Ecodesign Directive) is an example of such policy action.

Another critical policy lever is through government procurement frameworks, which can be strengthened to prioritise sustainable and low-carbon products and service models to support the proposed material and carbon reduction targets. This can be supplemented by public reporting of progress towards targets. Japan’s Ministry of the Environment, for example, discloses estimates of greenhouse gas reductions brought about by its green public procurement actions.

Economic growth and positive environmental outcomes are often viewed as a hard trade-off. However, in the case of the circular economy there are some clear solutions to overcome this dilemma: by maximising the productivity of the materials we use and, by doing so, reducing waste. This generates both economic and environmental benefits.

As Australia continues to rebuild from the pandemic and local natural disasters, there has never been a better time to focus on turning our waste and resource supply challenges into an opportunity for a stronger and more resilient economy.

Dr Kar Mei Tang is Chief Circular Economist with NSW Circular. Her work focuses on how environmental and economic policy can intersect to bring about better local and global outcomes. Her experience spans many years of senior executive and governance roles in these fields in the public and private sectors, in Australia and internationally.